After what seems an agonizingly long time since the first ideas of the book took root, I got the following letter from my publishers (how sweet that sounds!) last week,

After what seems an agonizingly long time since the first ideas of the book took root, I got the following letter from my publishers (how sweet that sounds!) last week,

“We are very pleased to inform you that your book has been published and it is available on http://tinyurl.com/jgn2djj. Customers can order it […] etc.”

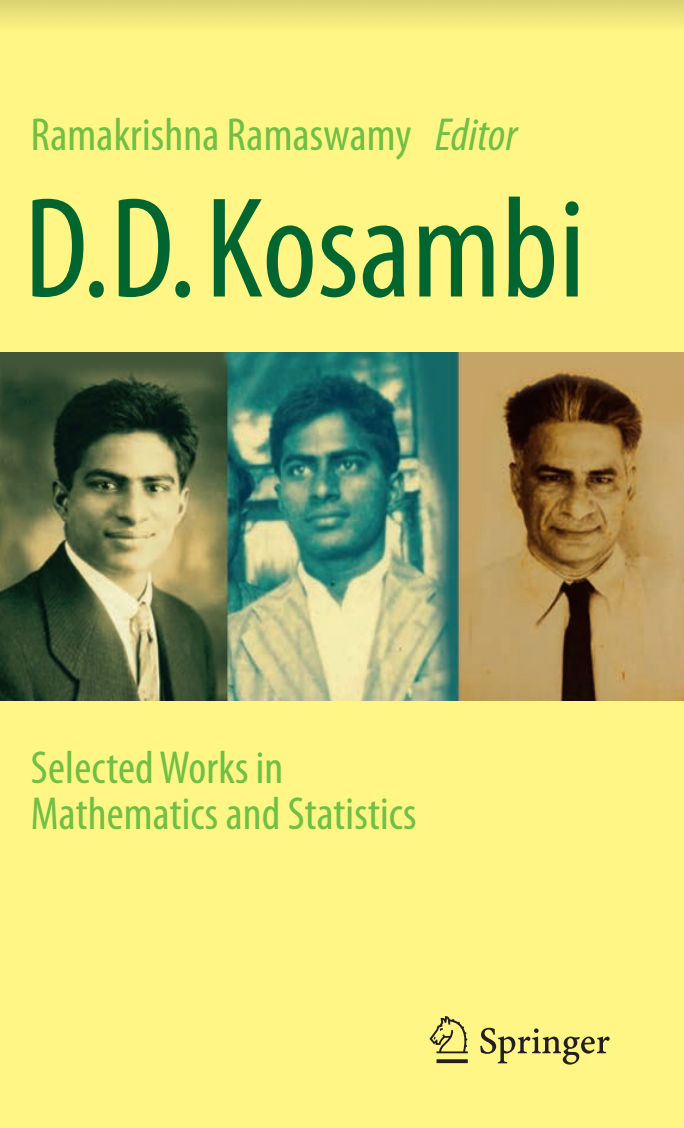

D D Kosambi: Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics is finally done, and is now available in both e and paper formats. The cover on the right shows DDK at three stages of his life, at Harvard, in Aligarh, and finally, in his TIFR years.

To quote from the blurb: This book fills an important gap in studies on D. D. Kosambi. For the first time, the mathematical work of Kosambi is described, collected and presented in a manner that is accessible to non-mathematicians as well. A number of his papers that are difficult to obtain in these areas are made available here. In addition, there are essays by Kosambi that have not been published earlier as well as some of his lesser known works. Each of the twenty four papers is prefaced by a commentary on the significance of the work, and where possible, extracts from technical reviews by other mathematicians.

My personal contribution to the book, other than to edit is, is fairly minimal. Apart from a preface, I have basically tried to describe the academic milieu in which Kosambi found himself at different points in his life, and have also tried to infer what others thought of him in another prefatory essay, “A Scholar in His Time”.

Kosambi gave his academic manifesto in the essay, “Adventure into the Unknown” which also is one of the places where he wrote that Science is the cognition of necessity. (It is quite another matter that the phrase is not one that can be understood in a straightforward manner. Anyhow, as a quote its famous enough.) Reprinting that essay in its entirety seemed appropriate, as also another note “On Statistics” that gives a flavour of DDK’s interdisciplinarity, mixing statistics, erudition, Marxism, etc. The last of the non-mathematical writings is a project completion report submitted by DDK to the Tata Trust in 1945 and it permits, among other things, an inner view of a vastly gifted and somewhat frugal scholar who, in parallel, and for Rs 1800, carried out 6 research projects on issues as diverse as writing a mathematical monograph on Path Spaces, editing a concordance of Bratrihari’s epigrams, and constructing an electromechanical computational device (the Kosmagraph), among others.

The remainder of the book is a set of reprints. Of his 67 or so papers in mathematics and statistics, about a third are presented, starting with some of his first papers, Precessions of an Elliptical Orbit and On a Generalization of the Second Theorem of Bourbaki, and ending with one of the papers he wrote under the peculiar alias of S. Ducray, Probability and Prime Numbers.

An attempt was made to include all the important papers, in particular the ones that made his reputation such as Parallelism and Path-Spaces that along with two other notes by Cartan and Chern are the basic of the Kosambi-Cartan-Chern theory, the various papers that laid the foundations of scientific numismatics, as well as the papers that he should have followed up but didn’t, such as Statistics in Function Space that foreshadowed the K-L decomposition. The Kosambi distance in genetics was elaborated in The Estimation of Map Distances from Recombination Values, and this is also reprinted.

Kosambi’s obsession with a statistical approach to the proof of the Riemann hypothesis resulted in several papers of which An Application of Stochastic Convergence, Statistical Methods in Number Theory, and The Sampling Distribution of Primes are reprinted here. These, as is well-known, effectively ruined his reputation as a serious mathematician.

Chinese. Japanese. French. German. English. DDK published papers in all these languages, sometimes exclusively, and twice the same article in translation. Also reprinted in this volume are three of the foreign language papers, the ones in German, French, and Chinese. The last is of particular interest since it was written during an exchange visit to China in the late 1950’s and only later published in English.

A number of people have helped me along the way and it is my pleasure to thank them all here. For the initial suggestion that the book be done, and for sustained and general encouragement, I am very grateful to Romila Thapar. I’ve written about this before. Meera Kosambi was keen to see her father’s mathematical legacy appreciated and was very enthusiastic about bringing out this collection and helped greatly in more ways than I can describe. She passed away in January 2015, when she knew the project was afoot, but not in any way certain as to how it would all come out. Michael Berry, S. G. Dani, and Andrew Odlyzko discussed and advised on various points of the mathematics. Indira Chowdhury and Oindrila Raychaudhuri helped vis-à-vis archival matters. Rajaram Nityananda had had many of DDK’s papers digitized, a great boon, and one that made the reproduction of some material much easier! Kapilanjan Krishan, Rahim Rajan, and Mudit Trivedi helped me locate some of the more obscure of DDK’s papers. K. Srinivas retyped almost all the papers, and Cicilia Edwin painstakingly proofread most of them. Toshio Yamazaki and Divyabhanusinh Chavda told me of their interactions with DDK, helping to flesh out the personality. Finally, Aban Mukherji was gracious with permissions, as were all the journal editors who kindly permitted the several articles to be reprinted.

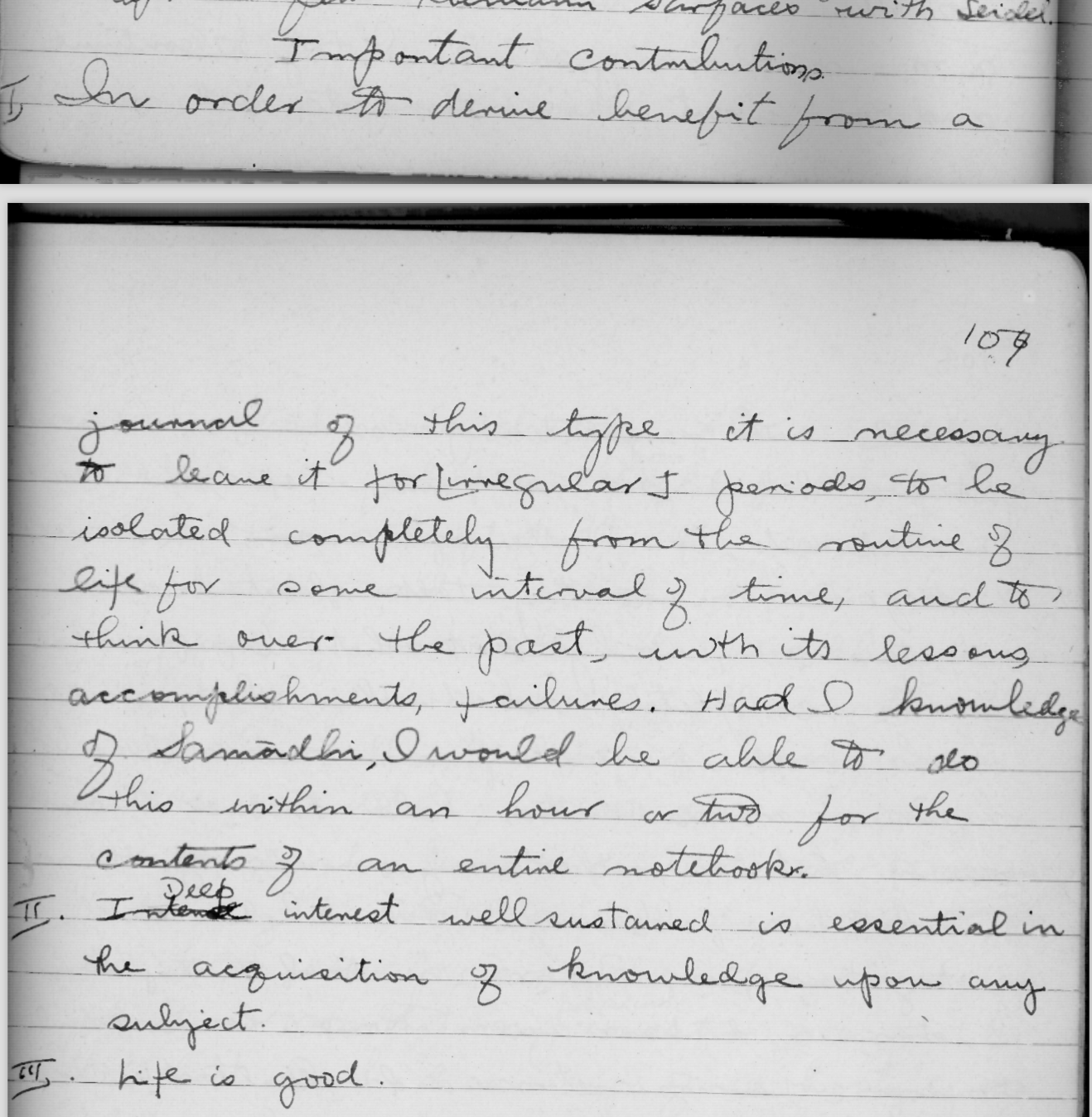

DDK maintained a charmingly frank notebook diary during his Harvard years. On the 19th of January 1927 he notes: A most restless day. I have forgotten to mention Monday the 17th and an important conference with Birkhoff thereon […] Problems: Fermat’s Last Theorem, the Four color map, the functional equation […] Today was unusually restless with a great deal of time spent, possibly wasted in the Widener. Looked up old issues of Outing, Shakespear’s Hindi Readers, most of Burton’s works [of him more later], Roosevelt on African and Brazilian ‘sporting’ – worthless – Stefansson’s excellent and much remembered ‘Friendly Arctic‘…

All this variety in a single day! To recall Wordsworth, Bliss indeed it was in that dawn to be alive! Kosambi, just out of his teens, was just bursting with energy, both intellectual and physical (for which one must read the diaries in some detail). The earnestness that only comes at that age shines through on the pages quite unselfconsciously:

Exuberance indeed, but also some simplicity: Deep interest, well sustained, is essential in the acquisition of knowledge upon any subject. And the third realization of the day: Life is good. Yes indeed, to be young was very heaven.

- D D Kosambi: Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics is published by Springer. ISBN: 978-81-322-3676-4

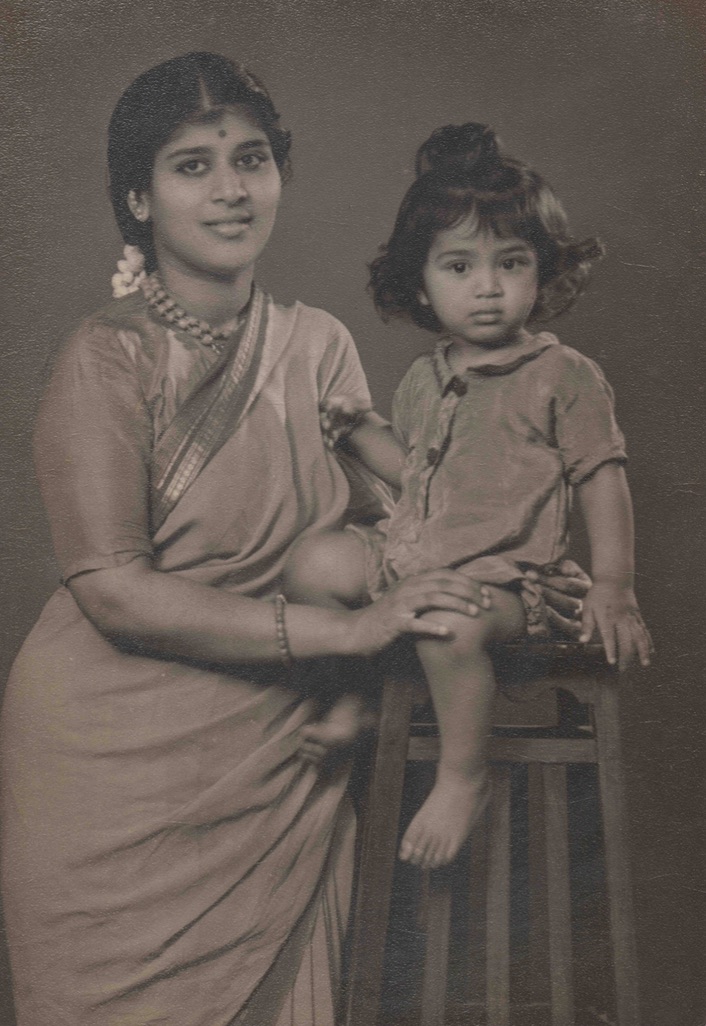

My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her:

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her:

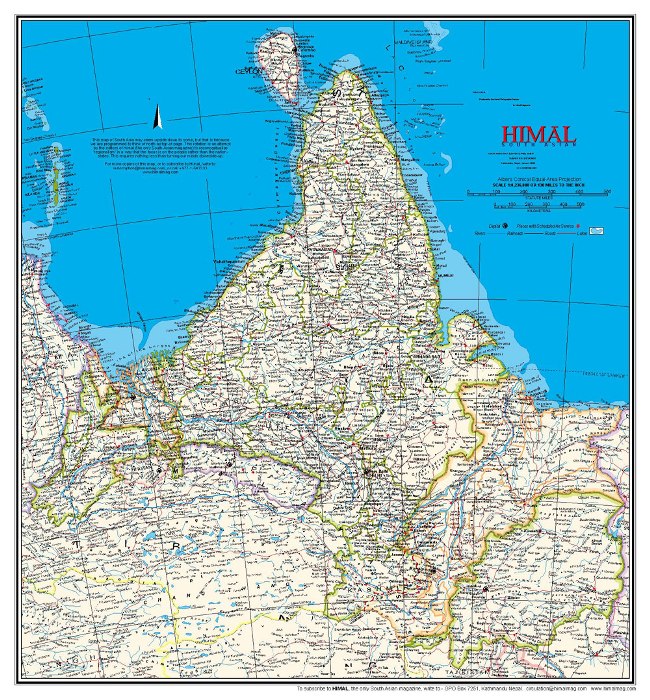

We are taught – those of us who have learned of the physical world – that there is no special place in space from which one should derive all our coordinates. There really is no preferred sense of direction other than by convention and by legacy. For many years now, I have had the Himal South Asia magazine’s unusual map hanging in my office and have had innumerable discussions (of a non-political kind) about how it helps to change one’s point of view about our country, whats up south and down north and so on. I must say that learning to see this map every working day (and learning to refer to it in as normal a fashion as possible) has also been instructive in its own way, and it seems more natural now to draw a line from Kanyakumari down to Kashmir rather than the other way around. To have any sense of nationalism hinge on a completely arbitrary definition of up or down is to have a somewhat unhinged sense of nationalism.

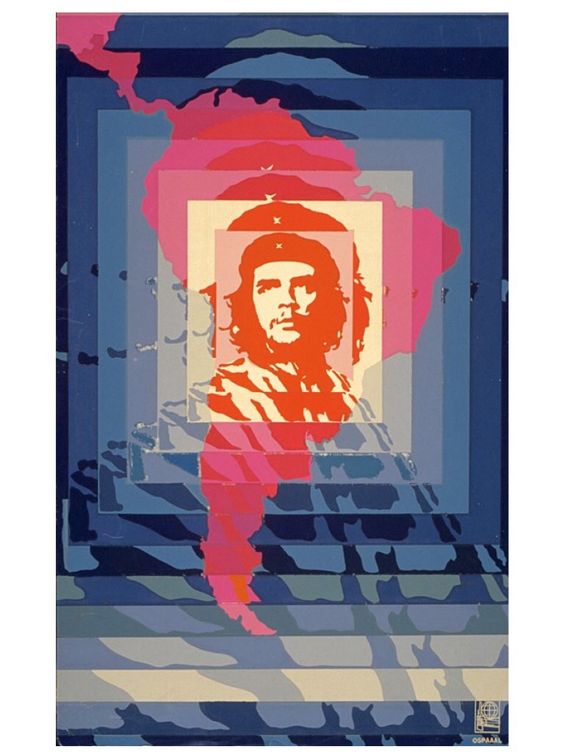

We are taught – those of us who have learned of the physical world – that there is no special place in space from which one should derive all our coordinates. There really is no preferred sense of direction other than by convention and by legacy. For many years now, I have had the Himal South Asia magazine’s unusual map hanging in my office and have had innumerable discussions (of a non-political kind) about how it helps to change one’s point of view about our country, whats up south and down north and so on. I must say that learning to see this map every working day (and learning to refer to it in as normal a fashion as possible) has also been instructive in its own way, and it seems more natural now to draw a line from Kanyakumari down to Kashmir rather than the other way around. To have any sense of nationalism hinge on a completely arbitrary definition of up or down is to have a somewhat unhinged sense of nationalism. And speaking of ultra-leftist, another thing that hangs in my office is (what I consider) a superb poster, a telescopic image of Ché Guevara on the South American continent… something I picked up forty years ago when it was fresh and new, and another thing I have had to explain to any number of visitors who eventually all come down to “Ah… JNU, what else can one expect?” But this is just one poster, and it is more about the kind of aesthetic I cared about at some point in time rather than some ideology that is indelibly tattooed onto my soul.

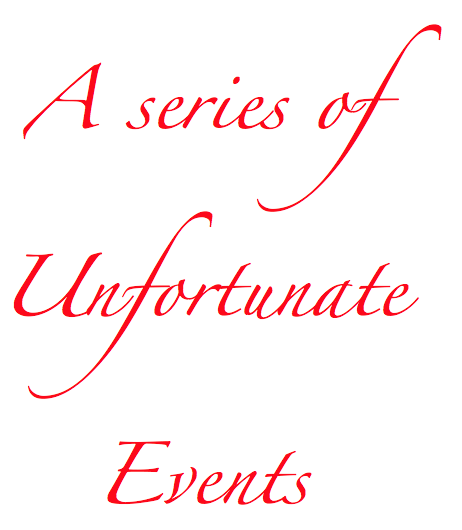

And speaking of ultra-leftist, another thing that hangs in my office is (what I consider) a superb poster, a telescopic image of Ché Guevara on the South American continent… something I picked up forty years ago when it was fresh and new, and another thing I have had to explain to any number of visitors who eventually all come down to “Ah… JNU, what else can one expect?” But this is just one poster, and it is more about the kind of aesthetic I cared about at some point in time rather than some ideology that is indelibly tattooed onto my soul. I’ve had to travel to Bangalore to chair a panel discussion on the 27th January, and to minimise my time away from Delhi, I decided to go out on the 26th and return on the 27th. I had asked my assistant at the office (which shall remain nameless) to book my tickets. On the 26th, I reached Delhi’s T3 terminal at 11:30 for my flight that was scheduled to leave at 12:55, only to find that it was further delayed on account of fog, rain, and also the Republic Day Air Force flypast… So the first Unfortunate event (UE1) was that I reached Bangalore at 6:30 that evening, three hours after I should have been there, necessitating programme changes, etc. etc. I had only myself to blame – a little thought would have told me that it is madness to fly out of or into Delhi on Republic Day with the added security, but hindsight is no solace.

I’ve had to travel to Bangalore to chair a panel discussion on the 27th January, and to minimise my time away from Delhi, I decided to go out on the 26th and return on the 27th. I had asked my assistant at the office (which shall remain nameless) to book my tickets. On the 26th, I reached Delhi’s T3 terminal at 11:30 for my flight that was scheduled to leave at 12:55, only to find that it was further delayed on account of fog, rain, and also the Republic Day Air Force flypast… So the first Unfortunate event (UE1) was that I reached Bangalore at 6:30 that evening, three hours after I should have been there, necessitating programme changes, etc. etc. I had only myself to blame – a little thought would have told me that it is madness to fly out of or into Delhi on Republic Day with the added security, but hindsight is no solace. Although I was not allowed on that flight, I eventually made it back to Delhi by the next flight, although that wasn’t for another two hours, which means I got back a day later, on the 28th… In the process I had to cancel one ticket, buy another, cancel that, get a third, The details are dreary, but I also learned just how shoddy the so-called security at our airports is… I dare say that nobody thinks its that great anyhow, but we all go through the motions.

Although I was not allowed on that flight, I eventually made it back to Delhi by the next flight, although that wasn’t for another two hours, which means I got back a day later, on the 28th… In the process I had to cancel one ticket, buy another, cancel that, get a third, The details are dreary, but I also learned just how shoddy the so-called security at our airports is… I dare say that nobody thinks its that great anyhow, but we all go through the motions. UE3: Nobody checked the tickets that had been sent by email – not my secretary, not the office staff. Me neither.

UE3: Nobody checked the tickets that had been sent by email – not my secretary, not the office staff. Me neither. I came into the plane, and immediately faced UE9, and feeling somewhat like baby bear, I pointed out to the stewardess that someone had been sitting in my chair and he was still there… Very kindly, even after comparing the two boarding passes, she reassigned me to a new seat, and its number 13C should have warned me that that was indeed UE10. I settled in, retrieved my Keigo Higashino (Malice, by the way, and an excellent read!) listened to another attendant tell us in a loud voice and with considerable attention to detail just what to do if there was an emergency landing (I always pay attention to which handle I am supposed to pull), and suddenly a couple of other airlines staff rush in ask for my boarding pass, match the torn stub and ask me to get up. Alarm bells going off in my mind, it was surely UE11: Something is wrong with my ticket, and without explaining, they take my luggage off the plane and ask me to follow them, leading to

I came into the plane, and immediately faced UE9, and feeling somewhat like baby bear, I pointed out to the stewardess that someone had been sitting in my chair and he was still there… Very kindly, even after comparing the two boarding passes, she reassigned me to a new seat, and its number 13C should have warned me that that was indeed UE10. I settled in, retrieved my Keigo Higashino (Malice, by the way, and an excellent read!) listened to another attendant tell us in a loud voice and with considerable attention to detail just what to do if there was an emergency landing (I always pay attention to which handle I am supposed to pull), and suddenly a couple of other airlines staff rush in ask for my boarding pass, match the torn stub and ask me to get up. Alarm bells going off in my mind, it was surely UE11: Something is wrong with my ticket, and without explaining, they take my luggage off the plane and ask me to follow them, leading to  In all this, and I guess that’s one of the things that kept me reasonably equable, there were moments of comedy. One handler at the aerobridge asked me why I had come a month early for my flight! Another set of people asked me why I booked for February if I wanted to travel in January (although it was painfully obvious from the nature of my ticket that it was booked by someone else). But the cake, so to speak, was taken when they told me that they would have to rebook me on another flight, and the supervisor said that they had two flights, one at 10:45 pm and another at 00:45 am, and “

In all this, and I guess that’s one of the things that kept me reasonably equable, there were moments of comedy. One handler at the aerobridge asked me why I had come a month early for my flight! Another set of people asked me why I booked for February if I wanted to travel in January (although it was painfully obvious from the nature of my ticket that it was booked by someone else). But the cake, so to speak, was taken when they told me that they would have to rebook me on another flight, and the supervisor said that they had two flights, one at 10:45 pm and another at 00:45 am, and “ There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the  There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the

There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the  The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant

The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant  One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.

One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own. The difficulty of not stopping though, is exacerbated when the only thing one can do is academics… and the inability of even the most well-intentioned amongst us to

The difficulty of not stopping though, is exacerbated when the only thing one can do is academics… and the inability of even the most well-intentioned amongst us to  The question of what to do, as well as how and where… These and other such night-thoughts have tended to occupy my mind a bit more these days, more often than in the past. This year has necessarily been a time of summing up and one of re-evaluation.

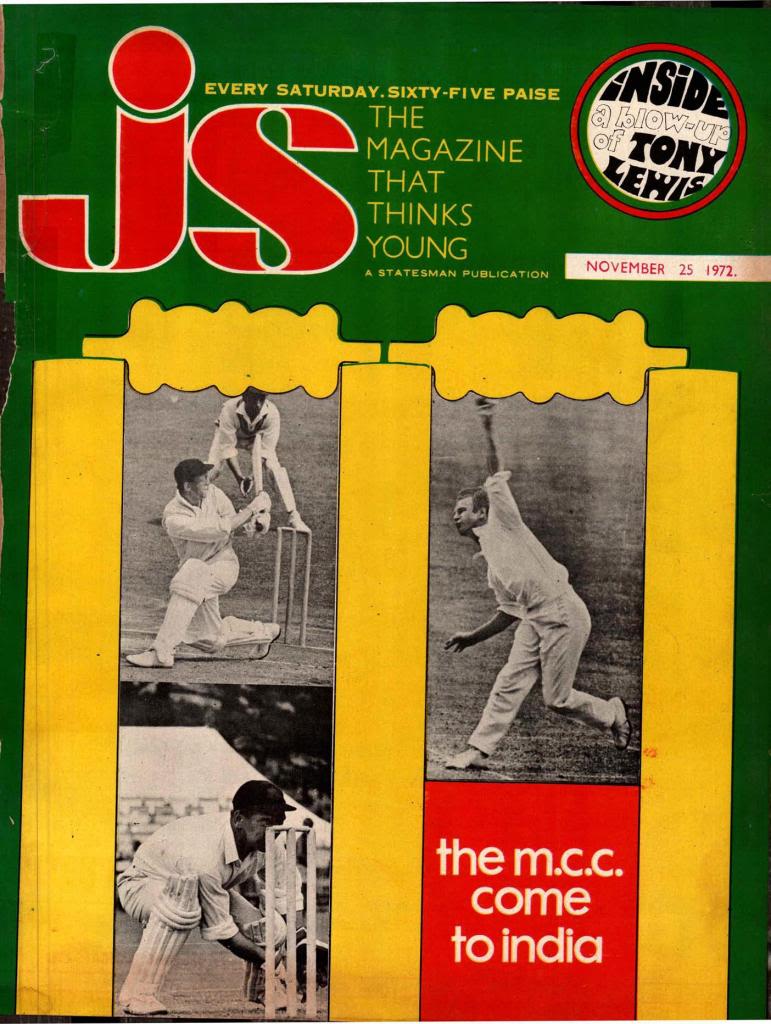

The question of what to do, as well as how and where… These and other such night-thoughts have tended to occupy my mind a bit more these days, more often than in the past. This year has necessarily been a time of summing up and one of re-evaluation. When I was in the last years of high school in Mussoorie, a brand new magazine appeared- JS, or Junior Statesman. The first issue came out in January 1967, and it quickly became staple reading for me and my friends, especially during long study periods when it was also forbidden… Although published from Calcutta (I remember going to Desmond Doig’s office once in 1970 or ’71) there was a lot of Kathmandu in it, drawings of hippies, articles by Jug Suraiya, Sashi Tharoor, Zeenat Aman, all exotic names in our boarding school. It was our one great weekly escape that we shared. When I went to college later, I went on to send contributions to JS (and earned some pocket money in the bargain), but regrettably I never kept copies, even though one of the articles I wrote even made it to a cover. And The Statesman has either not digitized this classic (or has chosen to not make the files public) and as a result, the only illustrations I was able to find on the net are very unsatisfactory. See above.

When I was in the last years of high school in Mussoorie, a brand new magazine appeared- JS, or Junior Statesman. The first issue came out in January 1967, and it quickly became staple reading for me and my friends, especially during long study periods when it was also forbidden… Although published from Calcutta (I remember going to Desmond Doig’s office once in 1970 or ’71) there was a lot of Kathmandu in it, drawings of hippies, articles by Jug Suraiya, Sashi Tharoor, Zeenat Aman, all exotic names in our boarding school. It was our one great weekly escape that we shared. When I went to college later, I went on to send contributions to JS (and earned some pocket money in the bargain), but regrettably I never kept copies, even though one of the articles I wrote even made it to a cover. And The Statesman has either not digitized this classic (or has chosen to not make the files public) and as a result, the only illustrations I was able to find on the net are very unsatisfactory. See above. I had already traveled outside India and found it quite underwhelming… One afternoon, driving beyond Tuensang in Nagaland, we stopped the jeep at a post along the road that said simply “Burma”. That was about it, but being a little over 14, I jumped out, ran into Burma, expecting I’m not sure what. Of course I could not have expected that it would be very different, but still, there was an unreasonable disappointment… And a year or so later, when living in Ukhrul in Manipur, we drove down to the border town of Moreh and crossed over into Tamu in Burma. Being heavily populated by Tamils at that time, it was actually possible to get by in Tamil, and the only sense of the foreignness of Tamu that I got was from the visibility of a lot of “Made in China” goods and Burmese parasols, neither of which were of interest to me then. But still, seeing the pagoda and having to change money into Kyat was a positive…

I had already traveled outside India and found it quite underwhelming… One afternoon, driving beyond Tuensang in Nagaland, we stopped the jeep at a post along the road that said simply “Burma”. That was about it, but being a little over 14, I jumped out, ran into Burma, expecting I’m not sure what. Of course I could not have expected that it would be very different, but still, there was an unreasonable disappointment… And a year or so later, when living in Ukhrul in Manipur, we drove down to the border town of Moreh and crossed over into Tamu in Burma. Being heavily populated by Tamils at that time, it was actually possible to get by in Tamil, and the only sense of the foreignness of Tamu that I got was from the visibility of a lot of “Made in China” goods and Burmese parasols, neither of which were of interest to me then. But still, seeing the pagoda and having to change money into Kyat was a positive… t some point in early 1969, I decided to go to Nepal. Some cajoling of parents was needed, but they gave in soon enough- there was little enough to do in Ukhrul, and those were also days in which, in retrospect, our lives seemed surreally secure. I was a little over 15, and all I had as I set off for Kathmandu was the address of some people at the Indian Embassy, friends of friends. My travel plan was vague. I would fly from Imphal to Calcutta (via Silchar and Agartala) by the Indian Airlines Dakota, take the train (third class, no reservation) to Patna, and fly into Kathmandu from there…

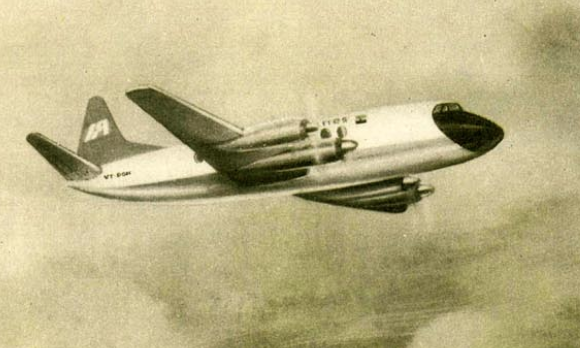

t some point in early 1969, I decided to go to Nepal. Some cajoling of parents was needed, but they gave in soon enough- there was little enough to do in Ukhrul, and those were also days in which, in retrospect, our lives seemed surreally secure. I was a little over 15, and all I had as I set off for Kathmandu was the address of some people at the Indian Embassy, friends of friends. My travel plan was vague. I would fly from Imphal to Calcutta (via Silchar and Agartala) by the Indian Airlines Dakota, take the train (third class, no reservation) to Patna, and fly into Kathmandu from there… I took some train to Patna and landed up early in the morning, and eventually made my way to the Indian Airlines city office by a rickshaw. I managed to get myself the very last seat on the morning flight to Kathmandu, and it is another testimony to the times that none of the IA staff (and from talking to some of the old-timers, I know that they all regret the merger with Air India) found it odd that I would be traveling on my own on an international flight. I can’t swear to it, but from the little scouting I have done on the web and the few old timetables I could find, I think it must have been IC 245, the thrice-weekly Vickers Viscount flight at 9:05 in the morning. That day we were a bit delayed by a massive dust storm – I have a very clear memory of the sky turning a vivid brown – but soon enough, I was in my window seat and on my way…

I took some train to Patna and landed up early in the morning, and eventually made my way to the Indian Airlines city office by a rickshaw. I managed to get myself the very last seat on the morning flight to Kathmandu, and it is another testimony to the times that none of the IA staff (and from talking to some of the old-timers, I know that they all regret the merger with Air India) found it odd that I would be traveling on my own on an international flight. I can’t swear to it, but from the little scouting I have done on the web and the few old timetables I could find, I think it must have been IC 245, the thrice-weekly Vickers Viscount flight at 9:05 in the morning. That day we were a bit delayed by a massive dust storm – I have a very clear memory of the sky turning a vivid brown – but soon enough, I was in my window seat and on my way… The window seat. Its funny what one chooses to remember – my eyes must have been glued to the outside for all the 50 minutes of the flight, but I can still see the roseate Himalayan peaks as we came into the Kathmandu valley in the early morning. Time has added hues and tinges to all memories, but I can still sense the excitement that I felt landing at Tribhuvan airport, more than a bit nervous since all I had was a school ID and an address in the Embassy compound that I needed to get to.

The window seat. Its funny what one chooses to remember – my eyes must have been glued to the outside for all the 50 minutes of the flight, but I can still see the roseate Himalayan peaks as we came into the Kathmandu valley in the early morning. Time has added hues and tinges to all memories, but I can still sense the excitement that I felt landing at Tribhuvan airport, more than a bit nervous since all I had was a school ID and an address in the Embassy compound that I needed to get to. And the arrival did not disappoint. In those days, all taxis in Kathmandu were whimsically painted in tiger stripes- and many were Volkswagen Beetles. The Tiger Taxis were a world away from the black and yellow Ambassadors of Calcutta and Delhi- but strangely I was only able to find a few images on the net. Anyhow, I was soon at the Embassy, and spent the subsequent few days doing much the usual things one did before there was Thamel.

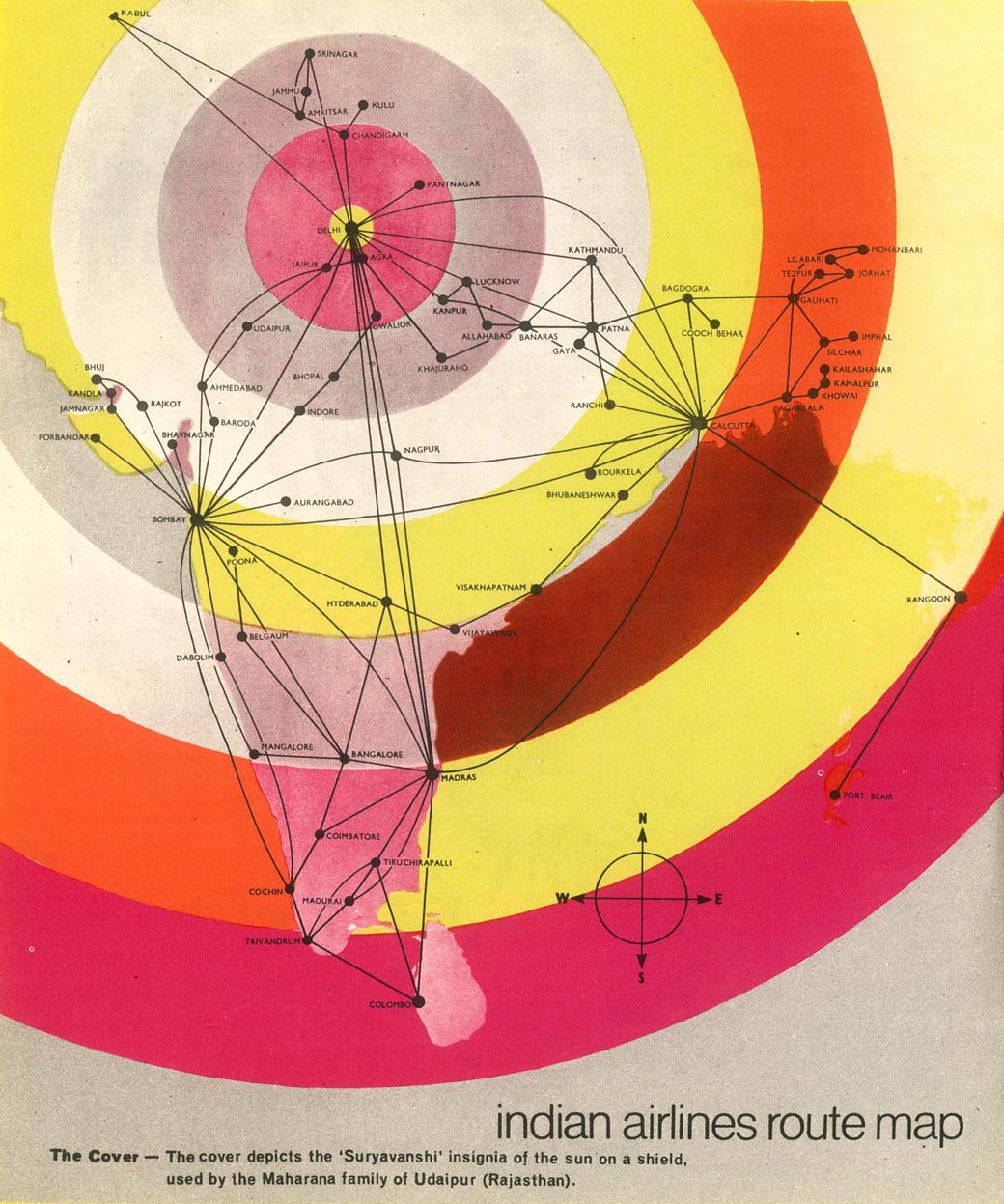

And the arrival did not disappoint. In those days, all taxis in Kathmandu were whimsically painted in tiger stripes- and many were Volkswagen Beetles. The Tiger Taxis were a world away from the black and yellow Ambassadors of Calcutta and Delhi- but strangely I was only able to find a few images on the net. Anyhow, I was soon at the Embassy, and spent the subsequent few days doing much the usual things one did before there was Thamel. I can’t decide whether Google and Google Maps are a good or poor way to recreate memories… There is so much that gets thrown up on a search that I’m not sure if these are my recollections or trancreations thereof. Anyhow, it has been a bonus to discover the old IC timetables and to realize that already in 1970, Indian Airlines flew between 62 cities in India. (The number today is not that much more within the country, while it has greatly increased the number of flights outside the country.) The train ride I took from Raxaul to Patna was via Muzaffarpur, and I do have a vivid memory of crossing the Ganga at Patna by ferry. These were the days before the Mahatma Gandhi Setu was built (as I discovered via G) or the Digha-Sonpur bridge… Blame it on the age, but the excitement of taking a boat trip- it was less than an hour long – to top off everything was a big bonus! And I can add in hindsight, it was one of the nicest ways in which I have arrived in Patna.

I can’t decide whether Google and Google Maps are a good or poor way to recreate memories… There is so much that gets thrown up on a search that I’m not sure if these are my recollections or trancreations thereof. Anyhow, it has been a bonus to discover the old IC timetables and to realize that already in 1970, Indian Airlines flew between 62 cities in India. (The number today is not that much more within the country, while it has greatly increased the number of flights outside the country.) The train ride I took from Raxaul to Patna was via Muzaffarpur, and I do have a vivid memory of crossing the Ganga at Patna by ferry. These were the days before the Mahatma Gandhi Setu was built (as I discovered via G) or the Digha-Sonpur bridge… Blame it on the age, but the excitement of taking a boat trip- it was less than an hour long – to top off everything was a big bonus! And I can add in hindsight, it was one of the nicest ways in which I have arrived in Patna. The practice of scientific research has evolved radically in the past few decades, largely due to the effects of globalization. Dramatically improved communication and significantly enhanced computation have contributed greatly to making scientific research a global enterprise. Many more scientific papers in many more areas of science today tend to involve large numbers of authors, and as the problems addressed become more complex, these different authors tend to be from different disciplines, often from different institutions, and quite often from different countries.

The practice of scientific research has evolved radically in the past few decades, largely due to the effects of globalization. Dramatically improved communication and significantly enhanced computation have contributed greatly to making scientific research a global enterprise. Many more scientific papers in many more areas of science today tend to involve large numbers of authors, and as the problems addressed become more complex, these different authors tend to be from different disciplines, often from different institutions, and quite often from different countries. It also brought to mind, oddly enough, The Lesson, that wonderful play by Ionesco that was such a staple of the amateur drama circuit when I was in college, and which is such a commentary on the nature of the teacher-student relationship and of pedagogy itself.

It also brought to mind, oddly enough, The Lesson, that wonderful play by Ionesco that was such a staple of the amateur drama circuit when I was in college, and which is such a commentary on the nature of the teacher-student relationship and of pedagogy itself. The contrasting styles of Hindustani and Carnatic classical music offer some parallels to these two pedagogic approaches. A night-long concert of Hindustani music may well be devoted to a single raga, developing and evolving a theme gradually. A Carnatic concert of a few hours, on the other hand would have several compositions in different ragas and with different tempi. There are those who swear by one and those that swear by another, but in the end, both have their adherents as well as those that simply don’t get either.

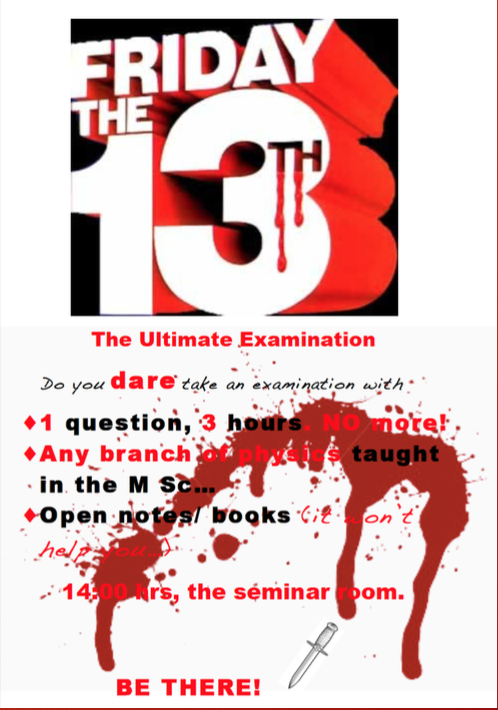

The contrasting styles of Hindustani and Carnatic classical music offer some parallels to these two pedagogic approaches. A night-long concert of Hindustani music may well be devoted to a single raga, developing and evolving a theme gradually. A Carnatic concert of a few hours, on the other hand would have several compositions in different ragas and with different tempi. There are those who swear by one and those that swear by another, but in the end, both have their adherents as well as those that simply don’t get either. But again, I digress. Modular teaching can lead to modularized learning, with some students feeling that specific topics belong to a specific courses (“… but Hermite polynomials are in quantum mechanics, not mathematical physics … “ or similar plaintive cries that can be heard when discussing the “unfairness” of a question paper…). And this is a concern that is shared by many. Graduate schools in the US often (if not uniformly) have comprehensives and cumulative examinations to address these types of issues, and quite successfully, but our teaching practices have not yet adopted such measures. Some years ago I offered the graduating batch of students in the MSc programme an optional examination after all the others were over. It happened to be a Friday, 13th May and hence the drama in the poster; the few students who took it were enthusiastic (if somewhat bewildered) but the answer scripts were more revealing of the outcomes of two years of teaching and learning…

But again, I digress. Modular teaching can lead to modularized learning, with some students feeling that specific topics belong to a specific courses (“… but Hermite polynomials are in quantum mechanics, not mathematical physics … “ or similar plaintive cries that can be heard when discussing the “unfairness” of a question paper…). And this is a concern that is shared by many. Graduate schools in the US often (if not uniformly) have comprehensives and cumulative examinations to address these types of issues, and quite successfully, but our teaching practices have not yet adopted such measures. Some years ago I offered the graduating batch of students in the MSc programme an optional examination after all the others were over. It happened to be a Friday, 13th May and hence the drama in the poster; the few students who took it were enthusiastic (if somewhat bewildered) but the answer scripts were more revealing of the outcomes of two years of teaching and learning… Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….”

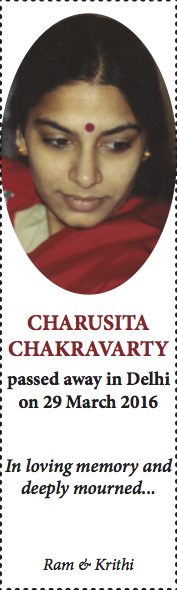

Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….”