When I was in the last years of high school in Mussoorie, a brand new magazine appeared- JS, or Junior Statesman. The first issue came out in January 1967, and it quickly became staple reading for me and my friends, especially during long study periods when it was also forbidden… Although published from Calcutta (I remember going to Desmond Doig’s office once in 1970 or ’71) there was a lot of Kathmandu in it, drawings of hippies, articles by Jug Suraiya, Sashi Tharoor, Zeenat Aman, all exotic names in our boarding school. It was our one great weekly escape that we shared. When I went to college later, I went on to send contributions to JS (and earned some pocket money in the bargain), but regrettably I never kept copies, even though one of the articles I wrote even made it to a cover. And The Statesman has either not digitized this classic (or has chosen to not make the files public) and as a result, the only illustrations I was able to find on the net are very unsatisfactory. See above.

When I was in the last years of high school in Mussoorie, a brand new magazine appeared- JS, or Junior Statesman. The first issue came out in January 1967, and it quickly became staple reading for me and my friends, especially during long study periods when it was also forbidden… Although published from Calcutta (I remember going to Desmond Doig’s office once in 1970 or ’71) there was a lot of Kathmandu in it, drawings of hippies, articles by Jug Suraiya, Sashi Tharoor, Zeenat Aman, all exotic names in our boarding school. It was our one great weekly escape that we shared. When I went to college later, I went on to send contributions to JS (and earned some pocket money in the bargain), but regrettably I never kept copies, even though one of the articles I wrote even made it to a cover. And The Statesman has either not digitized this classic (or has chosen to not make the files public) and as a result, the only illustrations I was able to find on the net are very unsatisfactory. See above.

But Kathmandu…

The gap between passing out of school and entering college was a long one: The Senior Cambridge exam was held in November 1968, and college admissions were not until June the following year. And for the not very professionally inclined – I was not going to do either medicine or engineering – there was a lot of time on my hands. As it happened, there was a to-do about the exams my year, and we all had to repeat the school final in February or March 1968, but still, there was a lot of waiting time, and I decided I wanted to travel “abroad”.

I had already traveled outside India and found it quite underwhelming… One afternoon, driving beyond Tuensang in Nagaland, we stopped the jeep at a post along the road that said simply “Burma”. That was about it, but being a little over 14, I jumped out, ran into Burma, expecting I’m not sure what. Of course I could not have expected that it would be very different, but still, there was an unreasonable disappointment… And a year or so later, when living in Ukhrul in Manipur, we drove down to the border town of Moreh and crossed over into Tamu in Burma. Being heavily populated by Tamils at that time, it was actually possible to get by in Tamil, and the only sense of the foreignness of Tamu that I got was from the visibility of a lot of “Made in China” goods and Burmese parasols, neither of which were of interest to me then. But still, seeing the pagoda and having to change money into Kyat was a positive…

I had already traveled outside India and found it quite underwhelming… One afternoon, driving beyond Tuensang in Nagaland, we stopped the jeep at a post along the road that said simply “Burma”. That was about it, but being a little over 14, I jumped out, ran into Burma, expecting I’m not sure what. Of course I could not have expected that it would be very different, but still, there was an unreasonable disappointment… And a year or so later, when living in Ukhrul in Manipur, we drove down to the border town of Moreh and crossed over into Tamu in Burma. Being heavily populated by Tamils at that time, it was actually possible to get by in Tamil, and the only sense of the foreignness of Tamu that I got was from the visibility of a lot of “Made in China” goods and Burmese parasols, neither of which were of interest to me then. But still, seeing the pagoda and having to change money into Kyat was a positive…

A t some point in early 1969, I decided to go to Nepal. Some cajoling of parents was needed, but they gave in soon enough- there was little enough to do in Ukhrul, and those were also days in which, in retrospect, our lives seemed surreally secure. I was a little over 15, and all I had as I set off for Kathmandu was the address of some people at the Indian Embassy, friends of friends. My travel plan was vague. I would fly from Imphal to Calcutta (via Silchar and Agartala) by the Indian Airlines Dakota, take the train (third class, no reservation) to Patna, and fly into Kathmandu from there…

t some point in early 1969, I decided to go to Nepal. Some cajoling of parents was needed, but they gave in soon enough- there was little enough to do in Ukhrul, and those were also days in which, in retrospect, our lives seemed surreally secure. I was a little over 15, and all I had as I set off for Kathmandu was the address of some people at the Indian Embassy, friends of friends. My travel plan was vague. I would fly from Imphal to Calcutta (via Silchar and Agartala) by the Indian Airlines Dakota, take the train (third class, no reservation) to Patna, and fly into Kathmandu from there…

Amazingly enough, it happened pretty much like that. I had an old sleeping bag and a duffel, some money- I’m not even sure how much, except that it was probably a few hundred rupees, a princely sum in those days- and an idea that Nepal was doable, and both exciting and inexpensive. In addition there were student concessions that made every trip half-price or less, and the Indian Airlines flights were adventures in of themselves. To this day I regret not taking the Agartala to Khowai flight when I could have- it was the shortest flight in the world at that time, and at Rs 7 ($1.40 then) surely the cheapest.

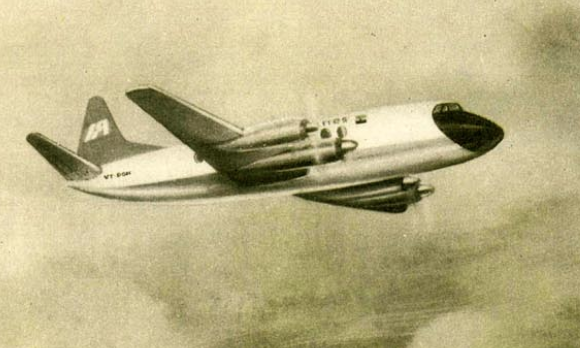

I took some train to Patna and landed up early in the morning, and eventually made my way to the Indian Airlines city office by a rickshaw. I managed to get myself the very last seat on the morning flight to Kathmandu, and it is another testimony to the times that none of the IA staff (and from talking to some of the old-timers, I know that they all regret the merger with Air India) found it odd that I would be traveling on my own on an international flight. I can’t swear to it, but from the little scouting I have done on the web and the few old timetables I could find, I think it must have been IC 245, the thrice-weekly Vickers Viscount flight at 9:05 in the morning. That day we were a bit delayed by a massive dust storm – I have a very clear memory of the sky turning a vivid brown – but soon enough, I was in my window seat and on my way…

I took some train to Patna and landed up early in the morning, and eventually made my way to the Indian Airlines city office by a rickshaw. I managed to get myself the very last seat on the morning flight to Kathmandu, and it is another testimony to the times that none of the IA staff (and from talking to some of the old-timers, I know that they all regret the merger with Air India) found it odd that I would be traveling on my own on an international flight. I can’t swear to it, but from the little scouting I have done on the web and the few old timetables I could find, I think it must have been IC 245, the thrice-weekly Vickers Viscount flight at 9:05 in the morning. That day we were a bit delayed by a massive dust storm – I have a very clear memory of the sky turning a vivid brown – but soon enough, I was in my window seat and on my way…

The window seat. Its funny what one chooses to remember – my eyes must have been glued to the outside for all the 50 minutes of the flight, but I can still see the roseate Himalayan peaks as we came into the Kathmandu valley in the early morning. Time has added hues and tinges to all memories, but I can still sense the excitement that I felt landing at Tribhuvan airport, more than a bit nervous since all I had was a school ID and an address in the Embassy compound that I needed to get to.

The window seat. Its funny what one chooses to remember – my eyes must have been glued to the outside for all the 50 minutes of the flight, but I can still see the roseate Himalayan peaks as we came into the Kathmandu valley in the early morning. Time has added hues and tinges to all memories, but I can still sense the excitement that I felt landing at Tribhuvan airport, more than a bit nervous since all I had was a school ID and an address in the Embassy compound that I needed to get to.

And the arrival did not disappoint. In those days, all taxis in Kathmandu were whimsically painted in tiger stripes- and many were Volkswagen Beetles. The Tiger Taxis were a world away from the black and yellow Ambassadors of Calcutta and Delhi- but strangely I was only able to find a few images on the net. Anyhow, I was soon at the Embassy, and spent the subsequent few days doing much the usual things one did before there was Thamel.

And the arrival did not disappoint. In those days, all taxis in Kathmandu were whimsically painted in tiger stripes- and many were Volkswagen Beetles. The Tiger Taxis were a world away from the black and yellow Ambassadors of Calcutta and Delhi- but strangely I was only able to find a few images on the net. Anyhow, I was soon at the Embassy, and spent the subsequent few days doing much the usual things one did before there was Thamel.

Getting back was another trip. I had run out of money, so flying back was not an option, and people told me about taking a bus to Birgunj, on the border between Nepal and India, from where one took a rickshaw to Raxaul on the Indian side. My memory of the ride is a dimmed one, the only striking image I have of that ride is when I looked over my shoulder for that last view of the Himalayas…

And then Birgunj. By the time the bus deposited me in Birgunj, it was dark, all the better for me to make the crossing I thought. I had bought some “foreign goods” – some inexpensive perfumes and gifts for my parents, mainly – and was firmly convinced that this would going to land me in trouble with the border police. Although I had hidden these artfully in my luggage in case of a search, I was quite nervous as we made the cross into Raxaul, and to the train station from where one would take the train back to Calcutta.

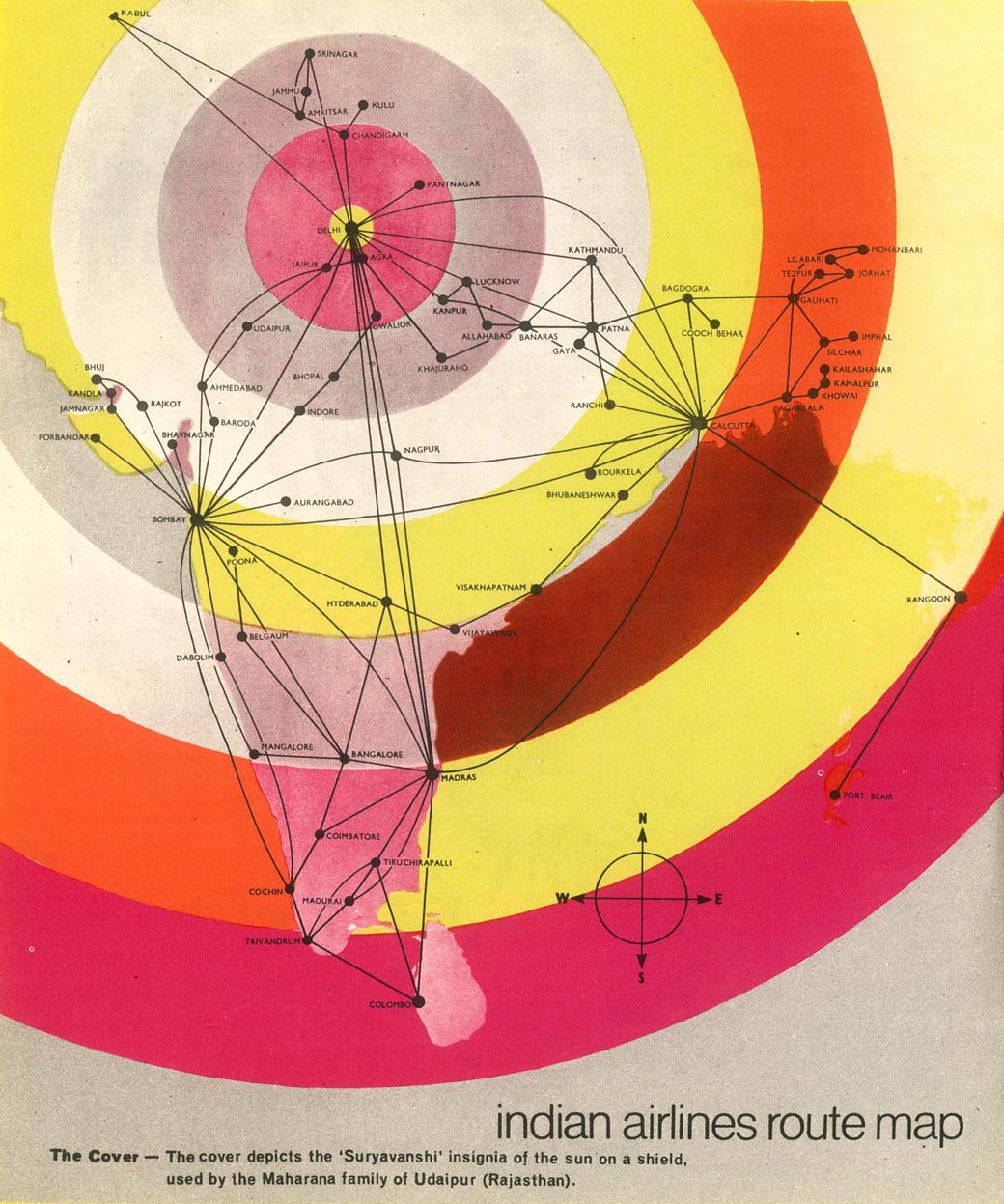

I can’t decide whether Google and Google Maps are a good or poor way to recreate memories… There is so much that gets thrown up on a search that I’m not sure if these are my recollections or trancreations thereof. Anyhow, it has been a bonus to discover the old IC timetables and to realize that already in 1970, Indian Airlines flew between 62 cities in India. (The number today is not that much more within the country, while it has greatly increased the number of flights outside the country.) The train ride I took from Raxaul to Patna was via Muzaffarpur, and I do have a vivid memory of crossing the Ganga at Patna by ferry. These were the days before the Mahatma Gandhi Setu was built (as I discovered via G) or the Digha-Sonpur bridge… Blame it on the age, but the excitement of taking a boat trip- it was less than an hour long – to top off everything was a big bonus! And I can add in hindsight, it was one of the nicest ways in which I have arrived in Patna.

I can’t decide whether Google and Google Maps are a good or poor way to recreate memories… There is so much that gets thrown up on a search that I’m not sure if these are my recollections or trancreations thereof. Anyhow, it has been a bonus to discover the old IC timetables and to realize that already in 1970, Indian Airlines flew between 62 cities in India. (The number today is not that much more within the country, while it has greatly increased the number of flights outside the country.) The train ride I took from Raxaul to Patna was via Muzaffarpur, and I do have a vivid memory of crossing the Ganga at Patna by ferry. These were the days before the Mahatma Gandhi Setu was built (as I discovered via G) or the Digha-Sonpur bridge… Blame it on the age, but the excitement of taking a boat trip- it was less than an hour long – to top off everything was a big bonus! And I can add in hindsight, it was one of the nicest ways in which I have arrived in Patna.

There really is not much more to tell. I got back to Calcutta the next day, took a plane the next to Imphal (via Agartala and Silchar) and reached Ukhrul, feeling very “foreign-returned” and worldly wise. I had had my share of sightseeing, the living goddess, Hanuman Dhoka, Pashupatinath, Swayambhunath, renting a bicycle and riding out to Patan, eating momos for the first time… the works, but as the wise TSE had said, it really was all about the journey.

The practice of scientific research has evolved radically in the past few decades, largely due to the effects of globalization. Dramatically improved communication and significantly enhanced computation have contributed greatly to making scientific research a global enterprise. Many more scientific papers in many more areas of science today tend to involve large numbers of authors, and as the problems addressed become more complex, these different authors tend to be from different disciplines, often from different institutions, and quite often from different countries.

The practice of scientific research has evolved radically in the past few decades, largely due to the effects of globalization. Dramatically improved communication and significantly enhanced computation have contributed greatly to making scientific research a global enterprise. Many more scientific papers in many more areas of science today tend to involve large numbers of authors, and as the problems addressed become more complex, these different authors tend to be from different disciplines, often from different institutions, and quite often from different countries.