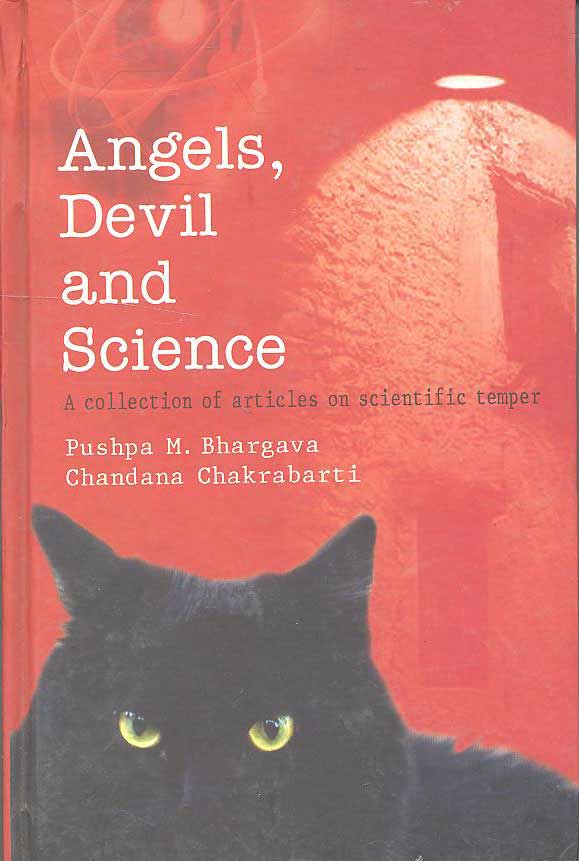

When I came to the University of Hyderabad in 2011, one of the first people I called upon was PMB, Pushpa Mittra Bhargava. Someone I had known in one or the other capacity since 1983, my most recent interaction with him then had been at a book release at the IIC, when my colleague at JNU, Prof. Bipan Chandra had asked me to be one of the speakers at the NBT release of PMB’s book Angels, Devils, and Science. I’ve forgotten now precisely what I said, but given my preoccupations at that time, I would have spoken of Kosambi, and Bernal, both rationalists who would have appreciated the argumentative Bhargava.

When I came to the University of Hyderabad in 2011, one of the first people I called upon was PMB, Pushpa Mittra Bhargava. Someone I had known in one or the other capacity since 1983, my most recent interaction with him then had been at a book release at the IIC, when my colleague at JNU, Prof. Bipan Chandra had asked me to be one of the speakers at the NBT release of PMB’s book Angels, Devils, and Science. I’ve forgotten now precisely what I said, but given my preoccupations at that time, I would have spoken of Kosambi, and Bernal, both rationalists who would have appreciated the argumentative Bhargava.

PMB was nothing if he was not complex. Fiercely loved by some of my friends, he was also as disliked by some others. He was outspoken, unapologetic, opinionated, he could be dismissive of others and very full of himself, but he was also always knowledgeable, erudite, and above all, genuine. By the time I got to know him, when he had more time to spend, it must also be admitted, he was already in his late 70’s. In 1983, though, he had invited me to CCMB to give a seminar, and I remember his interest at that time was on Manfred Eigen’s hypothesis on the origin of life, and whether something like life might have just happened by chance in the chaos of early Earth. From that early interaction, a scientific collaboration grew between Somdatta Sinha, staff member at CCMB and myself, resulting in three journal articles, and more importantly, a lifelong friendship (it helps also that we share a birthdate) that has outlived spouses and geographical dislocations. We wrote an article that has appeared today in The Wire, and I quote from it below, with permission.

Pushpa Mittra Bhargava – a.k.a. PMB – was larger than life. His flamboyance was multidimensional, from the striking printed bush-shirts he was very often seen wearing, to the scientific friends and colleagues he cultivated, to the remarkable institution that he built and causes he espoused. Never one to shy away from controversy, he was one of the most outspoken public scientists in the country, and one who stood his ground on political as well as scientific fronts. There have been few like him in terms of his personal courage, and fewer still who were as unafraid to be vocal on issues that challenged his personal convictions.

PMB, born in Ajmer in 1928, was educated in Lucknow. He obtained his PhD from Lucknow University in 1949 and shortly thereafter moved to Hyderabad, to work at the CSIR’s Regional Research Laboratory (RRL) as an organic chemist. Although he spent a few years in the US and in England, he remained a Hyderabadi for the rest of his life, and Hyderabad is where both of us got to know him more closely, although at different stages of our lives.

Like few other chemists in the country in the 1950s and 1960s, PMB was greatly taken up by the ‘molecular’ approach to biology. He was an evangelist, and as students we recall his efforts in the early 1970s in persuading the faculty and students of leading chemistry departments in the country to look into the then-nascent field of molecular biology. He campaigned with great energy for setting up the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), first within RRL Hyderabad (now called the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology) in 1977.

Although a separate campus was not established for the institute until the mid 1980s, he was able to attract some outstanding talent to CCMB as well as some stellar visitors – James Watson and Francis Crick among them. From its inception, the CCMB had a distinctive character, marked by a fresh and distinctly innovative approach. It was always a very special type of laboratory within the CSIR. PMB’s vision was evident on all scales, from the type of building to the art in the corridors, the groups that were formed and the problems that were studied.

In turn, two very distinctive features of PMB and his approach to institution building are worth noting. The first is the sense of aesthetics, his ability to integrate artistic sensibility into the work environment, something he shared with Homi Bhabha and C.V. Raman. Indeed, he paid close attention to the details of design and he prioritised aesthetics and functionality over all else, be it the CCMB or his own residential quarters.

The second was his belief in the need for scientists to speak up for the cause of science, and the need for public intellectuals to engage on contemporary issues in forums that were appropriate. He ensured that CCMB would have occasions to invite the common people to come see what science was being done there, but he would also make the lectures by leading scientists available to the public at large. He believed that it was the duty of scientists to fellow citizens to explain and encourage them to get excited by science, and think scientifically.

From the early 1980s to this day, thousands of school and college students and their parents, and countless others, would visit CCMB and learn from the faculty and students there as to what work was going on. Another of his passions was MARCH (Medically Aware and Responsible Citizens of Hyderabad), an organisation that he cofounded and which would meet every month to discuss some issue or other pertaining to public health. Given his sensibilities, these would be current and he would also get some of the leading experts to come and talk.

Of course, the cause of public engagement could take extreme forms. In 2015, he returned his Padma Bhushan (awarded to him in 1986) to the Government of India as a protest against the government’s attack on rationalism, reasoning and science. Years earlier, in 1994, he had resigned from the fellowship of the science academies of India for their lack of opposition to governmental plans to introduce astrology into university curricula. He spoke out against many issues, such as homoeopathy, GM crops, irrational beliefs and superstitions, pseudoscience and the lack of scientific temper, and about which there are numerous reports in the media. He responded to national issues with conviction and inevitably made enemies for his strong views and actions.

But what remain are indelible impressions of PMB the man. Both of us were associated with and influenced, in different ways, by him over a long period of time. Oddly enough, it was his intellectual curiosity that stimulated our academic collaboration, starting with an invitation to RRL to speak at the CCMB in 1983. At that time, SS had just joined CCMB as a young faculty member: fresh from JNU and working in an area of biology most people were unfamiliar with, and always ready to question the ‘administration’s decisions’.

PMB would listen patiently. Faculty meetings encouraged long discussions, dissent, arguments over institutional issues – and all this came largely from the sense of belonging that he instilled in the staff. Hugely nationalistic, in a way that was appropriate at that period of time, PMB would ask, “Why can we not do this work here?” of one or the other scientific problem. Keenly aware of trends in world science, he encouraged faculty to think of difficult and completely new problems that could have applications to society. He had the ability to find excellence and innovative ideas in people, independent of their rank or academic pedigree.

Regular group meetings with scientific literature reviews, a steady stream of national and international visitors whom the young faculty and PhD students always met, implementing a full technical group to support biologists with instrumentation issues, setting up a fully participatory and shared work atmosphere, and, most importantly, making young students and faculty feel the aura of basic science and giving the confidence of wanting to do interesting and difficult work, was PMB’s seminal contribution to the next generation of students and faculty.

There were also aspects of PMB that were difficult to deal with. Views that diverged widely from his were unsustainable. Those who could not convince him of their viewpoint either had to concur or leave. He could be arrogant, on many issues he was mistaken or inconsistent, and he could often seem autocratic and dogmatic. He had his blind spots. But for all his strong opinions, he had a commitment to quality, and in the end this is essential to build anything that will last.

And PMB was much more than even this. To people around him – students, young faculty, the lab-boys, gardeners, drivers, people who managed the instruments, air-conditioning, guesthouse and canteen, and others – he was intensely personal. Cutting across hierarchies, he was one of them, their own PMB. He made everybody feel that working together towards excellence in all spheres is the way to excel. CCMB was not only known for its science but also its cleanliness, beauty, reliably excellent facilities and the ability to have the scientific faculty, administration, engineering, stores and purchase, gardening and hospitality services work together smoothly, like a well-oiled machine.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that all this happened largely due to the contagious enthusiasm that PMB radiated. He was always there. This was a new approach to the directorial style, one that was uncommon in those days (and even now). He knew everybody by name and made it his job to know each person’s concerns. He made lab rules such that anybody could work at any time of day and night, but in a way that safety was never compromised. Support to all employees to be dropped back home at night after work, or if they were stuck in any emergency condition anywhere in India, and interactions allowing free discussions – these were all hallmarks of making one feel ‘at home’ in the workplace.

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting.

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting.

Shortly after I moved to New Delhi in 1986, I got to spend six weeks in Campinas, Brazil. On the way to the beach at Guarujá one weekend I drove with some friends through the not so picturesque town of Cubatão, which, as Wikipedia will gladly tell you, was one of the most polluted cities in the world, nicknamed “Valley of Death”, due to births of brainless children and respiratory, hepatic and blood illnesses. High air pollution was killing forest over hills around the city.

Shortly after I moved to New Delhi in 1986, I got to spend six weeks in Campinas, Brazil. On the way to the beach at Guarujá one weekend I drove with some friends through the not so picturesque town of Cubatão, which, as Wikipedia will gladly tell you, was one of the most polluted cities in the world, nicknamed “Valley of Death”, due to births of brainless children and respiratory, hepatic and blood illnesses. High air pollution was killing forest over hills around the city.

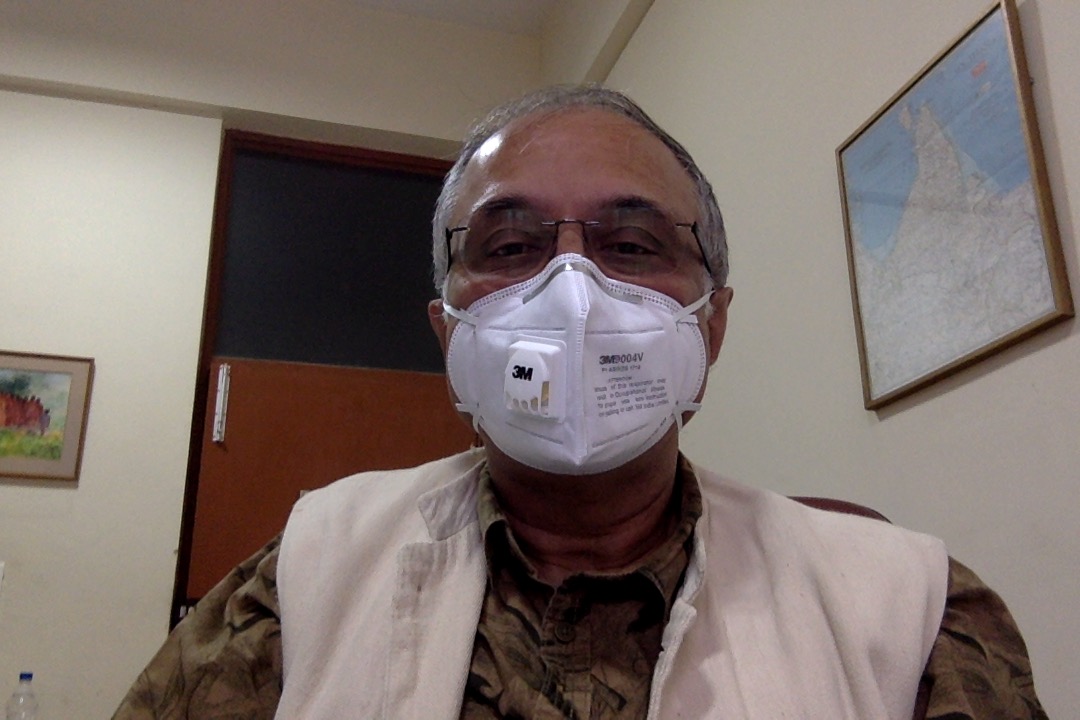

Breathing hurts. The eyes smart, one can feel the acidity (or so I imagine) of the air as it passes through one’s nostrils. It does not smell particularly bad always, but the air is not fresh by any stretch of the imagination. It is just impossible to take a deep breath and that has ruled out any exercise, even the most modest exertion. Schools were shut last week for a few days, but they have reopened, and there is little indication that serious political intervention is going to take place. The long term effects on us all, and on the environment is worth thinking about, else it may not be long before our city’s Wiki entry includes the epitaph “high air pollution killed Delhi’s urban forests”.

Breathing hurts. The eyes smart, one can feel the acidity (or so I imagine) of the air as it passes through one’s nostrils. It does not smell particularly bad always, but the air is not fresh by any stretch of the imagination. It is just impossible to take a deep breath and that has ruled out any exercise, even the most modest exertion. Schools were shut last week for a few days, but they have reopened, and there is little indication that serious political intervention is going to take place. The long term effects on us all, and on the environment is worth thinking about, else it may not be long before our city’s Wiki entry includes the epitaph “high air pollution killed Delhi’s urban forests”. Yesterday, in particular, was very difficult- even in my office in JNU, arguably one of the greener parts of Delhi, wearing a mask made it somewhat easier to breathe. I posted this picture on Facebook and was inundated with invitations to move to Kashmir, Hyderabad, Manipur, Melbourne, and ironically, São Paulo! I hear that things have improved there since the 1980’s so maybe its a good option. Cubatão, here I come!

Yesterday, in particular, was very difficult- even in my office in JNU, arguably one of the greener parts of Delhi, wearing a mask made it somewhat easier to breathe. I posted this picture on Facebook and was inundated with invitations to move to Kashmir, Hyderabad, Manipur, Melbourne, and ironically, São Paulo! I hear that things have improved there since the 1980’s so maybe its a good option. Cubatão, here I come!

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting.

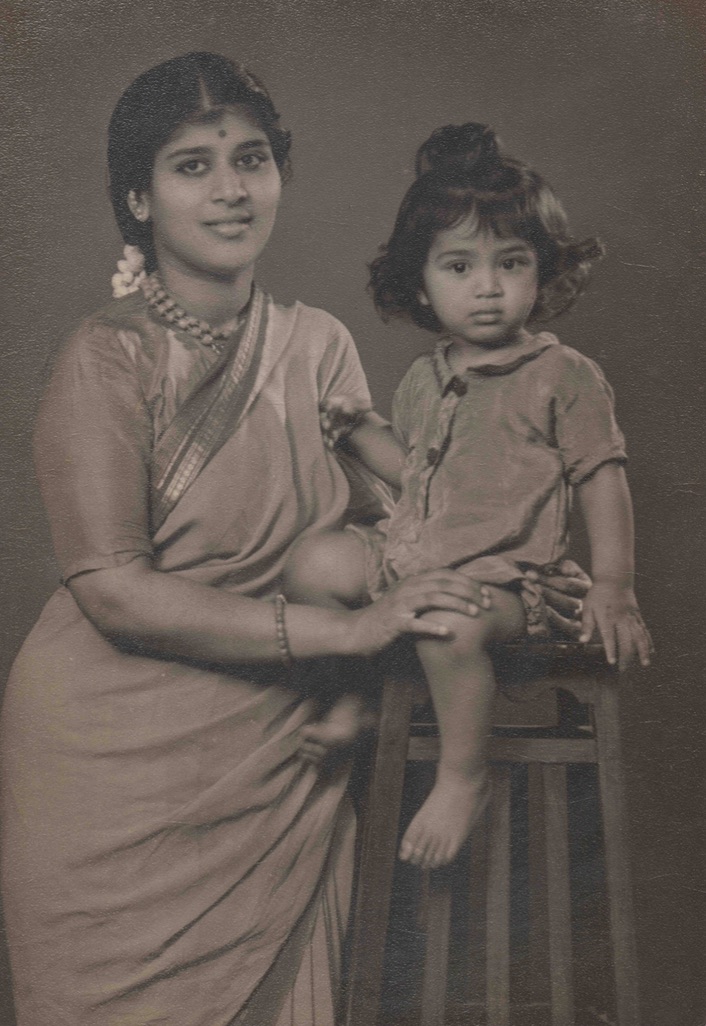

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting. My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her:

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her: Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….”

Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….” My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at

My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at