Actually a dozen of them, one being Very Unfortunate.

Not having Lemony Snicket to catalogue my tales of woe, I must be my own muse, writing this post on a somewhat bumpy and very late flight home. I should be more upset than I feel since I have managed to spend four hours in an airport on a day when I could have used that time more profitably, and something like eight or nine hours time on travel all told, just to get from Bangalore to Delhi. The easy answer to why I am not so upset would be age or experience or both, but I suspect that with the passing years, I have begun to expect unfortunate events (or UEs), a sort of retribution for various sins of the past. But I digress.

I’ve had to travel to Bangalore to chair a panel discussion on the 27th January, and to minimise my time away from Delhi, I decided to go out on the 26th and return on the 27th. I had asked my assistant at the office (which shall remain nameless) to book my tickets. On the 26th, I reached Delhi’s T3 terminal at 11:30 for my flight that was scheduled to leave at 12:55, only to find that it was further delayed on account of fog, rain, and also the Republic Day Air Force flypast… So the first Unfortunate event (UE1) was that I reached Bangalore at 6:30 that evening, three hours after I should have been there, necessitating programme changes, etc. etc. I had only myself to blame – a little thought would have told me that it is madness to fly out of or into Delhi on Republic Day with the added security, but hindsight is no solace.

I’ve had to travel to Bangalore to chair a panel discussion on the 27th January, and to minimise my time away from Delhi, I decided to go out on the 26th and return on the 27th. I had asked my assistant at the office (which shall remain nameless) to book my tickets. On the 26th, I reached Delhi’s T3 terminal at 11:30 for my flight that was scheduled to leave at 12:55, only to find that it was further delayed on account of fog, rain, and also the Republic Day Air Force flypast… So the first Unfortunate event (UE1) was that I reached Bangalore at 6:30 that evening, three hours after I should have been there, necessitating programme changes, etc. etc. I had only myself to blame – a little thought would have told me that it is madness to fly out of or into Delhi on Republic Day with the added security, but hindsight is no solace.

Now let me skip to the last, the Very Unfortunate Event 12. On my return journey on the 27th, around 8 pm when I was comfortably ensconced in my seat, waiting for the door to close and the plane to pull back, some air marshals arrived and asked me to follow them. I was taken off the plane…

Although I was not allowed on that flight, I eventually made it back to Delhi by the next flight, although that wasn’t for another two hours, which means I got back a day later, on the 28th… In the process I had to cancel one ticket, buy another, cancel that, get a third, The details are dreary, but I also learned just how shoddy the so-called security at our airports is… I dare say that nobody thinks its that great anyhow, but we all go through the motions.

Although I was not allowed on that flight, I eventually made it back to Delhi by the next flight, although that wasn’t for another two hours, which means I got back a day later, on the 28th… In the process I had to cancel one ticket, buy another, cancel that, get a third, The details are dreary, but I also learned just how shoddy the so-called security at our airports is… I dare say that nobody thinks its that great anyhow, but we all go through the motions.

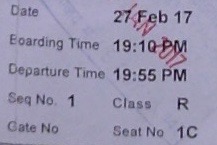

UE2 starts with the travel itinerary that I had asked for. Instead of sending me back from Bangalore to Delhi on the 27th January, the travel agency had actually made a booking for the 27th February.

UE3: Nobody checked the tickets that had been sent by email – not my secretary, not the office staff. Me neither.

UE3: Nobody checked the tickets that had been sent by email – not my secretary, not the office staff. Me neither.

UE4. On the 27th January, my assistant asked that I should be web checked-in, and the agency sent the boarding pass, leading to UE5, that I also didn’t check the boarding pass, a fragment of which is shown on the left.

Using this boarding pass for 27 February, I entered the Bangalore International Airport, waved in by the CISF staff who looked at the ticket and my JNU ID card. UE6. And UE7 was that I was also passed through security, another set of CISF chaps.

Being somewhat early at the airport, I tried to see if there was an earlier flight I could take, but I was already past security so it didn’t seem worth the hassle. Anyhow, by about 8 the flight was boarding and I tried to get in, and the first real jolt that all was not smooth was UE8, when I was briefly held up at the gate. Apparently someone else also had the boarding sequence 1 (I was mildly surprised that I was the first person to check in on the flight…). After a few minutes the very pleasant attendants told me to go ahead as it was OK. By now, nobody should be surprised that the CISF guards at the aerobridge waved me through after a perfunctory glance at my boarding pass.

I came into the plane, and immediately faced UE9, and feeling somewhat like baby bear, I pointed out to the stewardess that someone had been sitting in my chair and he was still there… Very kindly, even after comparing the two boarding passes, she reassigned me to a new seat, and its number 13C should have warned me that that was indeed UE10. I settled in, retrieved my Keigo Higashino (Malice, by the way, and an excellent read!) listened to another attendant tell us in a loud voice and with considerable attention to detail just what to do if there was an emergency landing (I always pay attention to which handle I am supposed to pull), and suddenly a couple of other airlines staff rush in ask for my boarding pass, match the torn stub and ask me to get up. Alarm bells going off in my mind, it was surely UE11: Something is wrong with my ticket, and without explaining, they take my luggage off the plane and ask me to follow them, leading to VUE12…

I came into the plane, and immediately faced UE9, and feeling somewhat like baby bear, I pointed out to the stewardess that someone had been sitting in my chair and he was still there… Very kindly, even after comparing the two boarding passes, she reassigned me to a new seat, and its number 13C should have warned me that that was indeed UE10. I settled in, retrieved my Keigo Higashino (Malice, by the way, and an excellent read!) listened to another attendant tell us in a loud voice and with considerable attention to detail just what to do if there was an emergency landing (I always pay attention to which handle I am supposed to pull), and suddenly a couple of other airlines staff rush in ask for my boarding pass, match the torn stub and ask me to get up. Alarm bells going off in my mind, it was surely UE11: Something is wrong with my ticket, and without explaining, they take my luggage off the plane and ask me to follow them, leading to VUE12…

There was a lot of waiting, some loss of composure, a few angry phone calls, and a colossal loss of time, but it was only then that I pieced together the banal mundanity of what had happened. The travel agency had issued a ticket for the wrong day, and including myself, no fewer than eight people had not realised the error over a 4 day period. And with a wrong ticket, I had made it all the way from the airport main gate to a seat on a plane that was about to take off… All of which would be laughable, of course, except that the obvious and absolute lack of care is more than a bit worrisome.

In the end I trundled home in the early hours of today with a little help from the airlines staff who do rise to the occasion. One of them was frank enough to confess that what I had gone through was a first for him… But there are always “explanations”: If you had only checked in your baggage, we would had spotted the mistake there. (Yes, but you also tell people to travel light and have now introduced no luggage fares, right?) If you had checked in before the other person with the same sequence number… right. Many ifs, but it also throws up some how comes.

- How come one can get a boarding pass a month in advance? Even the airlines staff were perplexed.

- How come three sets of CISF staff looked at my boarding pass and didn’t notice anything? So all they did was that they tallied the name with the photograph?

- The airlines make a big deal of scanning the tickets to verify identity. How come these readers don’t get a wrong date on the ticket?

This is a service industry after all, so the staff aim to please and are always quick to assume that some machine might have made a mistake somewhere. Machines do, but in this sad story, the biggest mistakes were human.

In all this, and I guess that’s one of the things that kept me reasonably equable, there were moments of comedy. One handler at the aerobridge asked me why I had come a month early for my flight! Another set of people asked me why I booked for February if I wanted to travel in January (although it was painfully obvious from the nature of my ticket that it was booked by someone else). But the cake, so to speak, was taken when they told me that they would have to rebook me on another flight, and the supervisor said that they had two flights, one at 10:45 pm and another at 00:45 am, and “Which would you prefer?”

In all this, and I guess that’s one of the things that kept me reasonably equable, there were moments of comedy. One handler at the aerobridge asked me why I had come a month early for my flight! Another set of people asked me why I booked for February if I wanted to travel in January (although it was painfully obvious from the nature of my ticket that it was booked by someone else). But the cake, so to speak, was taken when they told me that they would have to rebook me on another flight, and the supervisor said that they had two flights, one at 10:45 pm and another at 00:45 am, and “Which would you prefer?”

All in all, it took some doing and I am still a bit mystified by the series of linked unfortunate events, with every link in the chain breaking down… I feel a bit like Wodehouse’s Crumpet in The Great Hat Mystery and “prefer to think that the whole thing, as I say, has something to do with the Fourth Dimension. I am convinced that that is the true explanation, if our minds could only grasp it.”

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the  There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the

There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the  The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant

The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant  One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.

One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.