I was recently invited to Thrissur to speak at EMS-Smrithi, the annual meeting that commemorates EMS Namboodiripad. The CPM leader Prakash Karat has said of EMS that he “straddled the history of twentieth century Kerala and the Indian Communist movement in a manner which invokes awe. The word ‘history’ is what recurs in the Malayalam media while paying tributes to him. History maker, history’s man, epochal figure: these are some of the terms which underline the recognition that EMS was something bigger than a political leader.”

I was recently invited to Thrissur to speak at EMS-Smrithi, the annual meeting that commemorates EMS Namboodiripad. The CPM leader Prakash Karat has said of EMS that he “straddled the history of twentieth century Kerala and the Indian Communist movement in a manner which invokes awe. The word ‘history’ is what recurs in the Malayalam media while paying tributes to him. History maker, history’s man, epochal figure: these are some of the terms which underline the recognition that EMS was something bigger than a political leader.”

It was an unusual invitation, but one that I gladly accepted, in part because of the unusual setting, and the chance to rub shoulders with a very different group of people. Not all unfamiliar, but still. I had been asked to speak on “Critical thinking, scientific temper, and the role of the scientific community“, and while the essay will appear in print elsewhere, I thought I would share some of it in this blogpost, although given that these are ongoing concerns of mine, bits and pieces of what follows have appeared in other posts.

Investment in research or in scientific activity is ultimately a community decision – and given our political system, it is reflected in the way in which the budget for science is decided. Which in turn is determined by the party (or parties) we vote into power. The bulk of research in the country is therefore publicly supported, and one of the issues at hand is whether the results of publicly funded research need to be shared with the public that funded it.

Scientists therefore have the responsibility – even the moral obligation or duty – of accurately communicating their ideas and results. Of necessity, some of this will be restricted to an audience of peers, but increasingly, it is necessary to communicate the results of publicly funded research to a wider audience. In addition, there are fallacious and misleading statements on issues pertaining to science that are made by persons holding public office (mainly politicians, but also others that play a prominent role in society). Scientists and communicators of science share the additional responsibility of responding to such statements, regardless of how uncomfortable this might be.

India’s share in the world’s scientific enterprise has been steadily increasing over the years. It is well known that the scientific output of a country correlates strongly with the nominal GDP, but recent data suggests also that India’s contribution to the scientific literature (ranked sixth today) has been increasing at an even sharper rate, in contrast to the US, Japan or the EU. At the same time, India’s share of citations – a proxy for the quality of the research in terms of how useful it is considered by peers – is only ranked twelfth. Our role as consumers overtakes our role as contributors to the global knowledge pool.

There are numerous reasons for this, ranging from inadequate and subcritical funding of scientific research to a lack of a sufficiently large or competent body of scientists, namely the lack of a critical mass in most disciplines. It has even been suggested that Indians, either innately or due to our educational system, lack a truly innovative spirit, and thus our research tends to be derivative and incremental rather than being innovative and path-breaking.

One reason why this assumes particular significance is that the practice of scientific research has evolved radically in the past few decades, largely due to the effects of globalization. The combined effects of a vastly improved communication network and enhanced computational power have contributed greatly to making scientific research a global enterprise. Many more scientific papers in many more areas of science today tend to involve large numbers of authors, and as the problems addressed become more complex, these different authors tend to be from different disciplines, often from different institutions, and also often from different countries.

These changes have been brought about not just by globalization and enhanced communication and mobility, but also by the realization of shared scientific goals and the advantages of collaborative research. Looking at the patterns of scientific publication over the past fifteen or more years, one can conservatively estimate that between 10 and 15% of the papers that are published by Indians is in collaboration with researchers based outside India. If one were to restrict the count to the last decade, to high-impact journals, or to authors from the better-known institutes in the country, the proportion of papers which result from international collaborations is even higher.

Trust is a crucial component in carrying out such collaborative research. One has to believe in the reliability of results communicated by one’s collaborators, some of who one may not have even met. And as is becoming painfully evident there are numerous ways in which the trust can be broken. Deliberately, as in the cases of fraud, but also inadvertently, when cultural cues are misread and the work (or other) ethics of different cultures clash. In this context, having a properly articulated code of conduct that is generally accepted is very valuable. The difficulty of finding a universally acceptable code of conduct that can be encapsulated in something like a scientist’s Hippocratic Oath is a very real one. But there are many other ways in which this trust can be broken, and that is through public voices that speak of or for science.

The Science Academies of India, namely the Indian National Science Academy, the Indian Academy of Sciences, and the National Academy of Sciences of India are bodies that have some national responsibility for the maintenance of standards. From the mid 1930’s when they were all formed, they have tried to represent the best of Indian science, both in the practice of science as well as in its presentation, through publications, through engagement with the public, and by creating an independent and autonomous forum for the promotion of science. But in addition, there is also the Indian Science Congress, a body that has been in existence prior to Independence. The Prime Minister has traditionally attended at least the inaugural session of the Annual meeting of the Congress, and many national policies have been announced at these meetings.

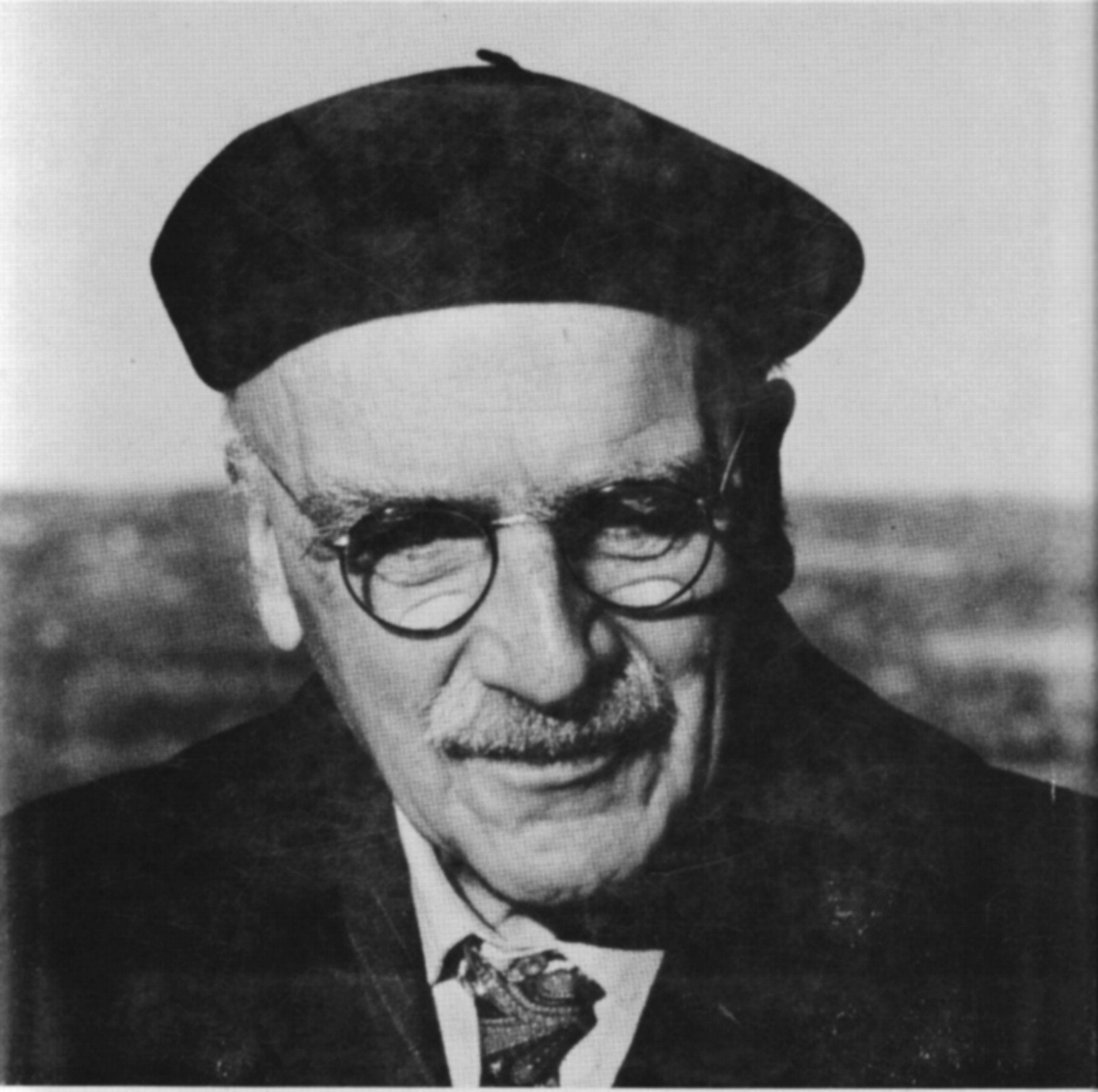

Over the years, though, the participation of politicians in what should be mainly a meeting of scientists has been unfortunate. On the one hand, the quality of the science at these meetings has been quite poor – JBS Haldane wrote a desperate essay, “Scandal of the Science Congress” describing his participation in the 1957 Congress, where he says, “I was privileged to hear the Prime Minister’s speech to the Association of Scientific Workers at the Science Congress recently held in Bombay. I did not hear his address to the Congress as a whole, since my ticket for this event had been thoughtfully removed from the booklet issued to me on arrival in Bombay. The Prime Minister made some rather bitter remarks about Indian Scientists who worked abroad because pay and facilities were better. […] It is time that responsible persons in India realised that the invitation of foreigners to such Congresses lowers the prestige of Indian science considerably. […] But the object of the Science Congress should be to advance science in India, and this, in my opinion, it failed to do. There would be little difficulty in making it useful. This would involve discourtesy to some influential people. But in science efficiency is more important than courtesy.”

Over the years, though, the participation of politicians in what should be mainly a meeting of scientists has been unfortunate. On the one hand, the quality of the science at these meetings has been quite poor – JBS Haldane wrote a desperate essay, “Scandal of the Science Congress” describing his participation in the 1957 Congress, where he says, “I was privileged to hear the Prime Minister’s speech to the Association of Scientific Workers at the Science Congress recently held in Bombay. I did not hear his address to the Congress as a whole, since my ticket for this event had been thoughtfully removed from the booklet issued to me on arrival in Bombay. The Prime Minister made some rather bitter remarks about Indian Scientists who worked abroad because pay and facilities were better. […] It is time that responsible persons in India realised that the invitation of foreigners to such Congresses lowers the prestige of Indian science considerably. […] But the object of the Science Congress should be to advance science in India, and this, in my opinion, it failed to do. There would be little difficulty in making it useful. This would involve discourtesy to some influential people. But in science efficiency is more important than courtesy.”

Haldane’s advice has not been heeded, and in recent years we have seen that the prestige of Indian science has been lowered considerably with very public and very irresponsible statements being made by responsible people on ancient Indian contributions to aerospace technology or reconstructive surgery or whatever. Especially when they are widely reported, such statements give a very negative image of the state of Indian science.

It is not just the lack of critical thinking that such statements betray, but they also indicate an intellectual laziness: there is no appeal to new evidence, no original or new research that uncovers any new data, and indeed the attempt is very much to create a fiction that suits a political narrative. In addition to a lack of data, there is also a deliberate attempt to ignore evidence – as for example regarding the migration of humans into the subcontinent, or more recently, the bizarre statements by the Minister of State for Human Resource Development who was quoted as saying that “Nobody, including our ancestors, in writing or orally, have said they saw an ape turning into a man. Darwin’s theory (of evolution of humans) is scientifically wrong. It needs to change in school and college curricula.”

In reaction, the three Science Academies of India issued a joint statement, “to state that there is no scientific basis for the Minister’s statements. Evolutionary theory, to which Darwin made seminal contributions, is well established. There is no scientific dispute about the basic facts of evolution. This is a scientific theory, and one that has made many predictions that have been repeatedly confirmed by experiments and observation. An important insight from evolutionary theory is that all life forms on this planet, including humans and the other apes have evolved from one or a few common ancestral progenitors.

It would be a retrograde step to remove the teaching of the theory of evolution from school and college curricula or to dilute this by offering non-scientific explanations or myths.

The theory of evolution by natural selection as propounded by Charles Darwin and developed and extended subsequently has had a major influence on modern biology and medicine, and indeed all of modern science. It is widely supported across the world.”

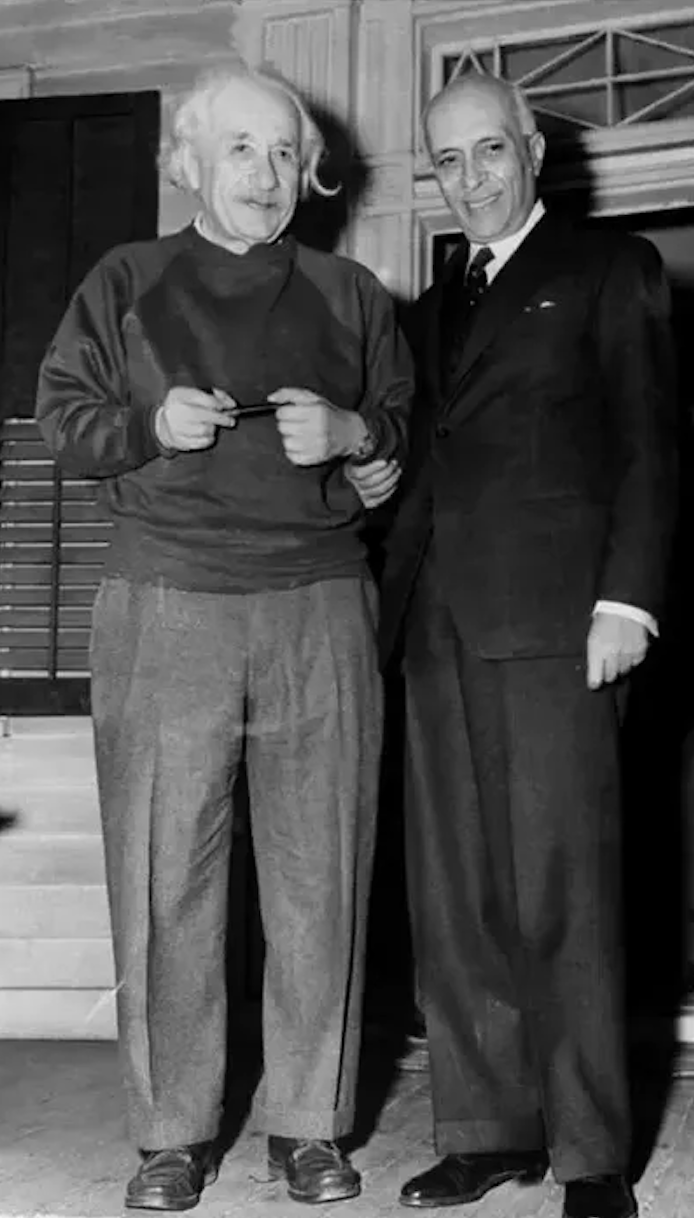

This incident points to an appalling lack of scientific temper in the public sphere. Scientific temper is a much abused term, and although it has been inserted in our Constitution, there is little real public understanding of what Nehru had in mind when he defined scientific temper in his Discovery of India as “a way of life, a process of thinking, a method of acting and associating with our fellow men“, namely that this was a characteristic general quality that we should absorb.

This incident points to an appalling lack of scientific temper in the public sphere. Scientific temper is a much abused term, and although it has been inserted in our Constitution, there is little real public understanding of what Nehru had in mind when he defined scientific temper in his Discovery of India as “a way of life, a process of thinking, a method of acting and associating with our fellow men“, namely that this was a characteristic general quality that we should absorb.

In January 2012, the National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources publicised the Palampur Statement, a resolution adopted at the International Conference on Science Communication for Scientific Temper. The Palampur Statement is a fairly long and comprehensive document that delves into, among other things, the changing world order, the current state of science and technology, the spread of fundamentalism, and so on. It has to be read- even cursorily would be enough- to get a true sense of its potential impact in our lives. One fragment that summarizes the main gist of it goes: the thought structure of a common citizen is constituted by scientific as well as extra-scientific spaces. These two mutually exclusive spaces co-exist peacefully. Act of invocation of one or the other is a function of social, political or cultural calling. Those who consider spreading Scientific Temper as their fundamental duty must aim at enlarging the scientific spaces. And it concludes: We call upon the people of India to be the vanguard of the scientific temper.

In vain. There is no noticeable increase in an appreciation of science in the public sphere. The suppression, or assassination, of rationalists – Kalburgi, Pansare, Dabholkar, Lankesh – point also to a persistence in public intolerance that education has done little to dispel. Many of the peoples’ science movements have noticeably decelerated, and paradoxically, the growth of the internet and social media have also seen an increase in fake news and misinformation, to the extent that another minister can assert, also at this year’s Science Congress, as it happens, that the late Stephen Hawking “said on record that our Vedas might have a theory which is superior to Einstein’s theory of E=mc2.”

So what role should the scientific community play in such matters? It is exhausting to counter every bullet of misinformation or false propaganda with public statements, but the fact that reactions are otherwise so slow in coming indicate that there is a lack of effective science communicators or more accurately, the lack of a critical mass of science communicators in the country. The West has had a long tradition of scientists themselves communicating their theories or discoveries with the public, be it Faraday and the Royal Society Lectures, or Eddington, Darwin, Huxley, Humboldt, and more recently, Sagan, Dawkins, Crick and Watson, and the like. The importance of communicating one’s ideas to whatever audience that shows an interest cannot be overstated. I’m not sure I want to get into whether it is a scientist’s moral obligation or duty to do so, but it does seem to me that the value of most things we do is enhanced when the communal nature of our activities is explicitly recognized. And the effectiveness of the work is directly related to the size and width of the community that is aware of or is made aware of it.

Investment in research or in scientific activity is ultimately a community decision – and given our political system, it is reflected in the way in which the budget for science is decided. Which in turn is determined by the party (or parties) we vote into power. The bulk of research in the country is therefore publicly supported, and one of the issues at hand is whether the results of publicly funded research need to be shared with the public that funded it. [The argument has been made very forcefully in the West, where research is funded both publicly and privately. When private companies fund research, the results are guarded zealously for possible patents, but many have argued for full public access to publicly funded research – and this has formed the vanguard of the Open Access movement.] One can take the point of view that the public in question do not have the required sophistication to appreciate the nuances, the finer details of most areas of research, and there is some truth in that. But the same argument would hold for, say, music, or cuisine, or poetry or any number of things that we enjoy as a community and appreciate as individuals. Each of us may hear the notes we wish to hear – or can hear, for that matter – and make of it what we will. There will be those among us for whom even this vague sense will provide the catalyst for other avenues of exploration and discovery.

Hearing about a subject from someone who has contributed greatly to it can be much more than just inspirational: the authenticity of experience transmits itself in a very unique manner. It is quite another thing to have someone else talk about it, though there are exceptions, of course- some science journalists are very effective communicators of the big picture, in a way that a practitioner who is focused on some small portion of the puzzle may not be. And of course, this is their forte, putting together a narrative that can grip a reader in a way in which an individual’s very personal story might not. But authenticity has a separate value and cannot be substituted. Which is why it might be good to occasionally worry about communicating just what it is that one does – science, poetry, or philosophy – to a wider and larger audience. The process might well be beneficial to the quality of what one does in the first place!

There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the trust of a society. By acknowledging this as part of a social contract, almost the very least one can do is to pay back to society by talking openly (and clearly) about what one does and the results one has obtained.

Almost all the research that is typically done at the University is publicly funded, through the Government of India via various ministries, or by other public funds. Should the results of such research not be made available to as many as possible? Willinsky’s Access Principle states that ‘a commitment to scholarly work carries with it the responsibility to circulate that work as widely as possible’. This is in part so that knowledge that is created can be disseminated in a manner that the largest numbers of people have unfettered access to it. Who ‘owns’ knowledge? The scholar who creates it through research, or the funding agency that funded it directly or indirectly, or the commercial publishing house who owns the journal where the research was reported? Should scholarly publications be absolutely freely available, or should they only reach those who have the funds to pay for subscriptions to the journals where these articles are published? There are as many nuanced opinions on this question as there are scholars, but with the ubiquity of the internet and the rising costs of journals, the issue is one that merits some thought and discussion.

The digital revolution is upon us all in a way that demands that such issues be thought about afresh since the modes of preservation of information and the modes of dissemination of knowledge have changed radically in our lifetime. For one thing, most journals of any quality are now online. Furthermore, many of them are ‘open access’, namely the articles they carry can be viewed without a subscription. However, the majority of academic journals have been in existence for a long time now and date back to the pre- digital era. The digitization of this legacy is a related issue, and the manner of the digitization and its consequent costs is relevant.

Openness is ‘better’ in an abstract way – at the end of the day it is not clear from which quarter the fundamental advances are going to come, and so it is best not to deny anyone the requisite opportunities. The more people who have access to knowledge, the more one can maximize the probability of any one of them using some part of it in a fundamental and future altering manner.

Willinsky proposes that access to knowledge is a fundamental human right, one that is closely related to the ability to defend other rights. The argument is tenuous but offers an interesting perspective on the ability of increased access to knowledge to have an impact beyond the areas envisioned by the creators of that knowledge. To some extent, the Right to Information Act in India has had a very similar effect – information on one aspect of public life can have consequences on other aspects.

Scholars should see that their work reaches the largest number of people and should make all efforts to ensure this. This is their dharma. Academic administrators should see that scholarly work is supported in a manner so as to have this wide reach. And this is their karma. In the long run, inclusivity is clearly more in the public interest than exclusion in any form, especially in a globalized world, and the Open Access movement can help us along this path.

Scholars should see that their work reaches the largest number of people and should make all efforts to ensure this. This is their dharma. Academic administrators should see that scholarly work is supported in a manner so as to have this wide reach. And this is their karma. In the long run, inclusivity is clearly more in the public interest than exclusion in any form, especially in a globalized world, and the Open Access movement can help us along this path.

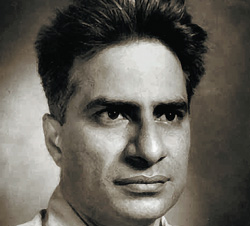

In closing, I would like to recall DD Kosambi’s essay, Science and Freedom, wherein he says “There is an intimate connection between science and freedom, the individual freedom of the scientist being only a small corollary. Freedom is the recognition of necessity; science is the cognition of necessity. The first is the classical Marxist definition of freedom, to which I have added my own definition of science.” Science, in Kosambi’s felicitous turn of phrase, is the process of acquiring knowledge and understanding – through thought and experience – of what is required, what is needed.

In closing, I would like to recall DD Kosambi’s essay, Science and Freedom, wherein he says “There is an intimate connection between science and freedom, the individual freedom of the scientist being only a small corollary. Freedom is the recognition of necessity; science is the cognition of necessity. The first is the classical Marxist definition of freedom, to which I have added my own definition of science.” Science, in Kosambi’s felicitous turn of phrase, is the process of acquiring knowledge and understanding – through thought and experience – of what is required, what is needed.

There is, as JD Bernal said so many years ago, hardly any country in the world that needs the application of science more than India. What is called for, therefore, is increased public investment, both intellectual and economic, in this necessary science and the cognition of this necessity.

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting.

He was one of the finest institution-builders in India as he could integrate the Indian culture of togetherness with the western culture of hard work. Several people who went on from CCMB to other institutions have tried to replicate such an ethos. So have several others who have seen it work so effectively at the CCMB. Beyond the flamboyance and everything else, PMB was a great inspiration. A friend and guide to many, his direct and indirect influence on Indian science and scientific culture will be lasting. There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the  There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the

There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the  The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant

The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant  One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.

One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.