I have stopped relying on serendipity; this has been replaced over the years by a firm belief in the hidden hand that unbeknownst to me puts things in my way, gives subtle signs, and guides me forward.

I have stopped relying on serendipity; this has been replaced over the years by a firm belief in the hidden hand that unbeknownst to me puts things in my way, gives subtle signs, and guides me forward.

A case in point was a chance reading of Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, an unlikely book for me to pick up early on a winter’s morning. Of course it might be said that a cold, foggy, and bleak morning is precisely the time to read about stoicism, but flipping through the pages, I came across his Letter 91, On the Lesson to be Drawn from the Burning of Lyons. The power of his writing aside, I am sorely tempted by the allegorical these days where everything is a metaphor for something else, something more immediate and more relevant.

The burning of Lyons so many centuries ago … the arson attacks on our public institutions … the erosion of trust, the destruction of edifices constructed with so much effort … all as one.

The value of reading Seneca is not just to draw moral lessons from the stoic philosophy, to control anger and passion in the face of so much provocation, but also to draw upon that wisdom and the hopes infused in that letter, written so many years ago.

The calamity, the fire that has wiped out the colony of Lyons, becomes in these days the calamity that has destroyed a great University, a great public institution. As Seneca says of the burning of Lyons, “Such a calamity might upset anyone at all, not to speak of a man who dearly loves his country. But this incident has served to make him inquire about the strength of his own character, which he has trained, I suppose, just to meet situations that he thought might cause him fear. I do not wonder, however, that he was free from apprehension touching an evil so unexpected and practically unheard of as this, since it is without precedent. […] Fortune has usually allowed all men, when she has assailed them collectively, to have a foreboding of that which they were destined to suffer.“

Somehow, we have all been just as unprepared for an evil so unexpected. So many great schools, to rewrite the Senecan text, any one of which would make a single institution famous, were wrecked in one term and with so little foreboding. And the strangeness of it all, the obscurity of purpose, adds immeasurably to the weight of this calamity, the death of a University.

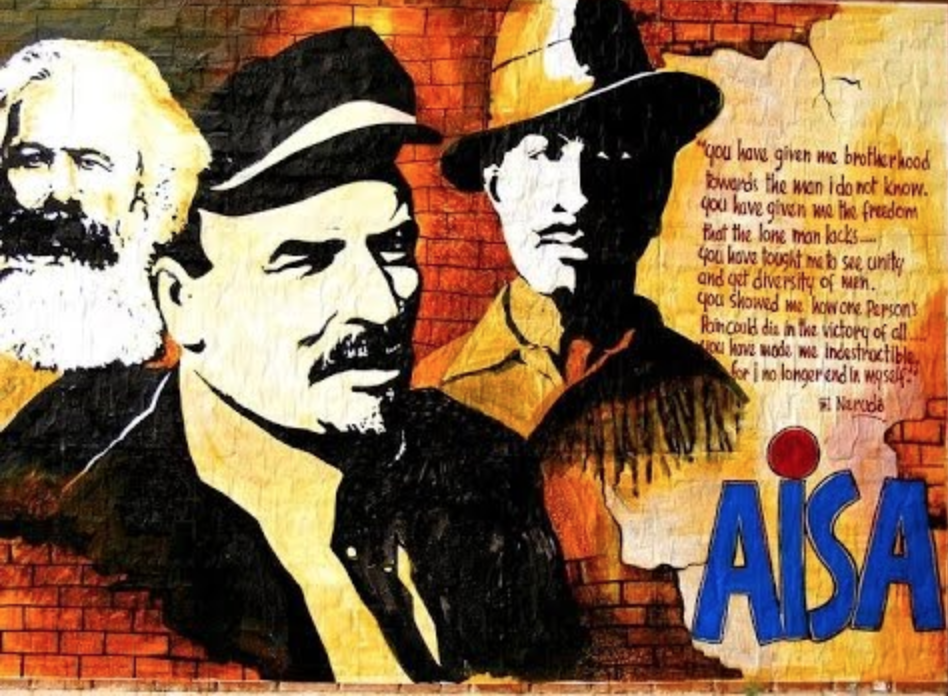

Of course I talk of our public Universitites, JNU in particular, of which I have talked earlier, and am not able to not talk about either. I continue to be surprised by the rapidity with which the spirit of the University has been crushed. Not for this institution, arguably a fine and great creation, “to be granted a period of reprieve before its fall.”

And the effect of this conflagration will last long – those who remember the old Lyons will not forget those who helped burn it down. And they, the ones that burn it now will not be able to forget what they have done.

As Seneca says, “nothing ought to be unexpected by us. Our minds should be sent forward in advance to meet all problems, and we should consider, not what is wont to happen, but what can happen. […] Chance chooses some new weapon by which to bring her strength to bear against us, thinking we have forgotten her.”

Stoicism therefore seems a wise strategy to follow. In the past few years, every time one has thought that the worst was over, some new horror has been thrust upon us. We should, as Seneca notes, therefore reflect upon all contingencies, and should fortify our minds against the evils which may possibly come.

Like Machiavelli’s or Kautilya’s, some of Seneca’s writings are lessons in leadership, notably his advice to Nero, On Mercy. And there are bits of this essay that advise leaders, as well as others. Commenting on the rapidity with which disastrous changes can be wrought, his observation that Whatever structure has been reared by a long sequence of years, at the cost of great toil and through the great kindness of the gods, is scattered and dispersed by a single day is a timeless warning against hubris, a warning that the present dispensations might well heed. And others as well.

Seneca’s own life was so filled with contradictions that he was quite attuned to the fickleness of fortune and very sensitive to the whims of successive Roman Emperors, at least two of who – Caligula and Nero – who had ordered him to commit suicide… Therefore let the mind be disciplined to understand and to endure its own lot, and let it have the knowledge that there is nothing which fortune does not dare – that she has the same jurisdiction over empires as over emperors, the same power over cities as over the citizens who dwell therein. We must not cry out at any of these calamities. Into such a world have we entered, and under such laws do we live. If you like it, obey; if not, depart whithersoever you wish. Cry out in anger if any unfair measures are taken with reference to you individually; but if this inevitable law is binding upon the highest and the lowest alike, be reconciled to fate, by which all things are dissolved.

Seneca’s own life was so filled with contradictions that he was quite attuned to the fickleness of fortune and very sensitive to the whims of successive Roman Emperors, at least two of who – Caligula and Nero – who had ordered him to commit suicide… Therefore let the mind be disciplined to understand and to endure its own lot, and let it have the knowledge that there is nothing which fortune does not dare – that she has the same jurisdiction over empires as over emperors, the same power over cities as over the citizens who dwell therein. We must not cry out at any of these calamities. Into such a world have we entered, and under such laws do we live. If you like it, obey; if not, depart whithersoever you wish. Cry out in anger if any unfair measures are taken with reference to you individually; but if this inevitable law is binding upon the highest and the lowest alike, be reconciled to fate, by which all things are dissolved.

There is also hope in the stoic outlook. Already there are signs that some changes are afoot. Like Lyons, which eventually was rebuilt, “to endure and, under happier auspices, for a longer existence!“, maybe we will bounce back, and the JNU of the future will be an even better University. Inshallah!

None of which can account for the slow and painful killing of an excellent university. And what lies at the heart of this heinous action is the basic incomprehension of what a modern university is, or indeed what a modern Indian university should be.

None of which can account for the slow and painful killing of an excellent university. And what lies at the heart of this heinous action is the basic incomprehension of what a modern university is, or indeed what a modern Indian university should be.

There were also some not so pleasant aspects of being at JNU. One was the two culture divide, caused in part by the huge disparity in size between the science Schools and the much larger Schools of International Studies, Language, and Social Sciences. The SPS was very small, even after we started the MSc in Physics, in 1991 or 1992. The students were younger and there were more of them, but still we were a mere ripple in the JNU, and some of the rules and regulations that were needed for a small cohort were not always in consonance with what the larger body had decided. But we went along, for the most part happy to be part of a public university, and adapting to the changes that were needed.

There were also some not so pleasant aspects of being at JNU. One was the two culture divide, caused in part by the huge disparity in size between the science Schools and the much larger Schools of International Studies, Language, and Social Sciences. The SPS was very small, even after we started the MSc in Physics, in 1991 or 1992. The students were younger and there were more of them, but still we were a mere ripple in the JNU, and some of the rules and regulations that were needed for a small cohort were not always in consonance with what the larger body had decided. But we went along, for the most part happy to be part of a public university, and adapting to the changes that were needed. Which is why, when in 2017 or 2018, the University administration does not condescend to talk to students let alone treat them as sentient beings capable of making their own choices, it seems an aberration. To be fair to the Administration (with the capital A) they do not talk to teachers either – unless one conforms to an archaic mode of conduct- but in the process, the entire University, teachers and students alike, is given the “Daddy knows best” line, and it is up to us to conform.

Which is why, when in 2017 or 2018, the University administration does not condescend to talk to students let alone treat them as sentient beings capable of making their own choices, it seems an aberration. To be fair to the Administration (with the capital A) they do not talk to teachers either – unless one conforms to an archaic mode of conduct- but in the process, the entire University, teachers and students alike, is given the “Daddy knows best” line, and it is up to us to conform.