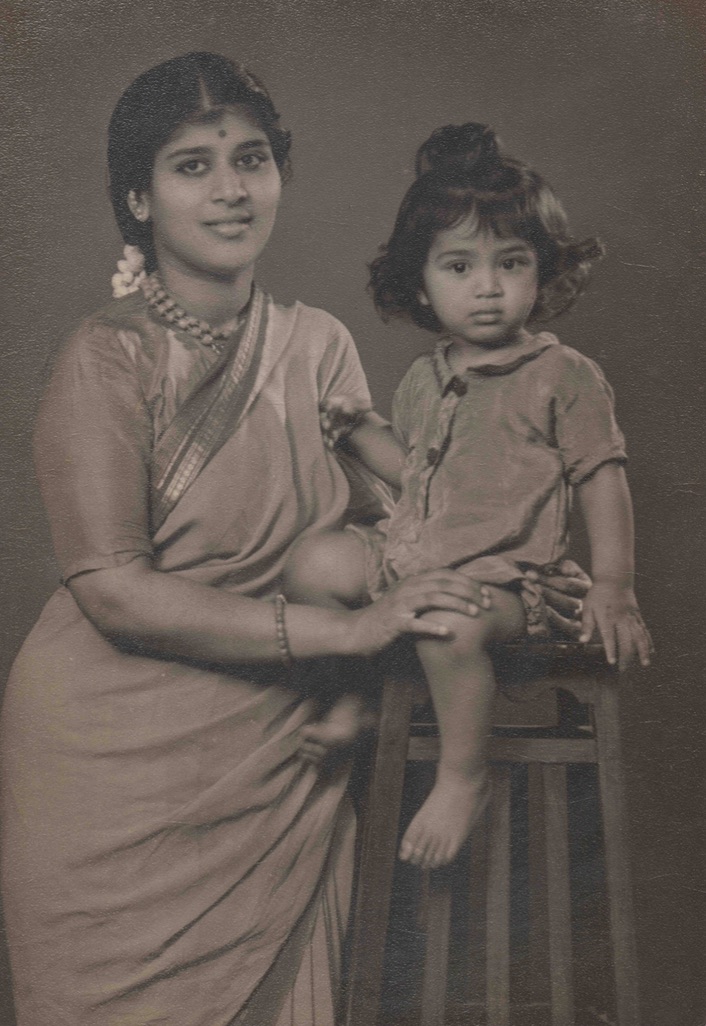

My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

My mother, Malathi Ramaswamy, who passed away in Chennai last month, was a little over eighteen when I was born. This photo on the left, of the two of us, was taken some time in 1954 in Madras, a short while before we left to join my father who was then posted in Srinagar.

Sometime last year she completed a memoir of her childhood and wrote about the Madras that has all but vanished. This was mostly to tell us, our children, and her sisters’ children and grandchildren what little she remembered of her childhood and of those times. Ironically, she went a few days before the final printed copies of the book could be delivered to her, but she knew it was in the making.

The book, titled ALLATHUR VILLA: Nathamoony Chetty and the story of our family is available to read online, and it tells of how my grandmother, Seethalakshmi, was adopted by Allathur Nathamoony Chetty across caste and linguistic boundaries and a huge economic gradient. My mother and my four aunts grew up speaking Telugu at home, Tamil outside, and compared to the rest of their family, were much better off. When any of the five of them would talk about those days, it was always a magical world that they conjured up: the contrasts, the improbability, the role of chance…

Their home, the Allathur Villa of the title, is gone now; sold, torn down, and in its place on Poonamallee High Road, stands a hotel. A few days ago, S Muthiah who does The Hindu’s Metroplus column talked about the book: The tales a house tells.

Many tales indeed. Married at sixteen, my mother entered a very different world as an Army-officer’s wife. She must have imbibed much from her Chetty grandfather during her growing years though, since I can scarcely recall a time when she was not working. First as a school-teacher, shifting from one school to the other around the country as and when my father was posted, and then, after a longer stay in Delhi, as a tourist guide.

And eventually, as an entrepreneur. She found her métier as a tour operator when in the mid 1970’s she and my father founded a travel company in Delhi. Over the next thirty or so years, they promoted tours and accompanied them. From Kashmir to Nagaland, there were few parts of India that she had not traveled through. And as it happened, many parts of the world as well.

The picture above, of her sitting in a truck on the India-Bhutan border shows her at her happiest: traveling, taking people around the country, and being appreciated for it. Her enthusiasm was infectious, as was her optimism – she was the introduction to India for many people, particularly those who came here to explore handicrafts. Some years ago, she and those who had traveled with her described these various journeys on her website, Speaking with Hands. One of these friends of hers wrote to us recently to say that “Malathi has been an inspiration to many with her fierce love, intense interest and devotion to her beloved India. She was a woman of great integrity and conviction fused with love and compassion… She will be missed, by so many.“

Like many women who were moving into the business world on their own in the 1970’s and 1980’s she had to write her own rules, and that was not always easy. Not for her, and frequently, also not for those around her… And she always had a project or two, was ever exploring, a characteristic that was admirable (and I did tell her that occasionally, even though it was often not easy to take). She did not shy away from trying to learn, whether it was trying out a new cellphone or laptop, or even reading difficult essays on the nature of modern physics.

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her:

Never at rest, till the end she was always looking forward to that next bit of travel, that next journey, and that next step. These words from Eliot, I suspect would have resonated quite strongly with her:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

The difficulty of not stopping though, is exacerbated when the only thing one can do is academics… and the inability of even the most well-intentioned amongst us to

The difficulty of not stopping though, is exacerbated when the only thing one can do is academics… and the inability of even the most well-intentioned amongst us to  The question of what to do, as well as how and where… These and other such night-thoughts have tended to occupy my mind a bit more these days, more often than in the past. This year has necessarily been a time of summing up and one of re-evaluation.

The question of what to do, as well as how and where… These and other such night-thoughts have tended to occupy my mind a bit more these days, more often than in the past. This year has necessarily been a time of summing up and one of re-evaluation. Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….”

Commenting on my last post, an old classmate wrote to say “Ram, we are both at an age where we mark the passage of time by composing eulogies for our friends and loved ones. One day someone else will do the same for us….” My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at

My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at