The University community is deeply saddened by the news the Professor S Nagarajan passed away on the 6th of January. He had retired from the service of the University quite some time ago in 1989, but for something like a dozen years he was one of the stalwarts of our Department of English. This is a great loss to the world of scholarship, and as Professor Narayana Chandran remarks, “Nagarajan, the scholar and friend, will be missed by many here and abroad, [and] thousands of his students and colleagues will be deeply saddened by the news of his passing”.

The University community is deeply saddened by the news the Professor S Nagarajan passed away on the 6th of January. He had retired from the service of the University quite some time ago in 1989, but for something like a dozen years he was one of the stalwarts of our Department of English. This is a great loss to the world of scholarship, and as Professor Narayana Chandran remarks, “Nagarajan, the scholar and friend, will be missed by many here and abroad, [and] thousands of his students and colleagues will be deeply saddened by the news of his passing”.

Another colleague, Professor S Viswanathan adds “the fraternity of English teachers in particular and the academics in general and the community of scholars and critics worldwide have lost one of the remnants of stalwarts cast in the heroic and morally upright mode. He was a pioneer even as a relatively young person and much later in the latter phase of his career at the University of Hyderabad in setting up a research and postgraduate department. The Department of English and the School of Humanities owe a great deal to his presence in them as the leader.”

A brief biography of Professor Sankalapuram Nagarajan (1929 – 2014) has been provided by Prof. Narayana Chandran: He was educated at Mysore, Nagpur, and Harvard, began teaching English at an early age. His career started in Mysore (1948– 1953) but he later served the Government of Madhya Pradesh as Assistant Professor in colleges across the state (1953– 1961). The then-Madhya Pradesh government insisted that all its servants pass a basic literacy test in Hindi, a directive that caused him some hardship. Nagarajan was however happy to leave his job for a Fulbright Fellowship in the United States. This Fellowship, again, was hard-won, considering Nagarajan’s insistence that he would accept it on condition that he be permitted to work on a topic of his choice, viz., Shakespeare’s Problem Plays, an insistence the Fulbright Foundation found rather difficult to respect initially, given their commitment to promoting the study of American literature and culture in India. Nagarajan’s third appearance before the Foundation to explain his ideas on the Problem Plays not only won him the coveted Smith-Mundt-Fulbright Scholarship (1958– 60) and the Harvard University Fellowship (1959– 60) but strengthened his life-long commitment to the profession of English and American Studies in India, both specialties which he pioneered and propagated in at least two leading Indian Universities for more than three decades.

On his return from the US, Nagarajan joined Poona University Department of English (Reader, 1961– 64; Professor, 1964– 77). He founded a full-fledged postgraduate research Department of English at Poona and continued to be the ex officio Chair of the English Board of Studies until 1977 and coordinated the English-teaching activities of its affiliated centres and colleges for well over a decade. He was also the first Coordinator of Summer Intensive Courses for English teachers (that somewhat forerun the present Refresher Courses in the UGC Staff Colleges) for which he sought funding from the American and British cultural agencies in India. Among his other substantial contributions include the introduction of research in American, Indian-English, and Commonwealth Literatures and Critical Theory; and the addition of regular updated catalogues in the Humanities and cutting-edge books and journals to the Jayakar Library. Few colleagues in India know that the very first dissertation on an Indian English topic and the most influential first book on Indian English fiction were written under his supervision in Poona by Paul C. Verghese and Meenakshi Mukherjee respectively. C. D. Narasimhaiah of Mysore University and he were the founding directors of the American Studies Research Centre in Hyderabad (now called the Osmania University Centre for International Programmes).

Among his many academic honours Nagarajan prized most his Clare Hall Visiting Fellowship at Cambridge University (1987). The following year, Clare Hall elected him a Life Member, a rare honour because the membership was recommended by the Estate of Professor I. A. Richards whose special lectures Nagarajan had attended during the professor’s Harvard visit in the early 60’s. Other honours had preceded Clare Hall— the Fellowship of Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington D.C.; Leverhulme Fellowship at the Australian National University, Canberra; Staff Fellowship of the Association of Commonwealth Universities at the University of Edinburgh; and the National Fellowship of the UGC, India. An unusually incisive scholar and commentator, Nagarajan excelled in philological and interpretive scholarship, a sampling of which would include his masterful Signet Classic edition of Measure for Measure (1964; rev. 1990), and his essays and notes in such esteemed journals as Shakespeare Quarterly, Essays in Criticism, The Sewanee Review, Modern Fiction Studies, Comparative Literature, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, College English, Notes & Queries, ESQ, World Literature Today, The Arnoldian, etc. His papers have been widely cited and indexed in all the Humanities Indices and reviews of English scholarship across the world.

Among his many academic honours Nagarajan prized most his Clare Hall Visiting Fellowship at Cambridge University (1987). The following year, Clare Hall elected him a Life Member, a rare honour because the membership was recommended by the Estate of Professor I. A. Richards whose special lectures Nagarajan had attended during the professor’s Harvard visit in the early 60’s. Other honours had preceded Clare Hall— the Fellowship of Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington D.C.; Leverhulme Fellowship at the Australian National University, Canberra; Staff Fellowship of the Association of Commonwealth Universities at the University of Edinburgh; and the National Fellowship of the UGC, India. An unusually incisive scholar and commentator, Nagarajan excelled in philological and interpretive scholarship, a sampling of which would include his masterful Signet Classic edition of Measure for Measure (1964; rev. 1990), and his essays and notes in such esteemed journals as Shakespeare Quarterly, Essays in Criticism, The Sewanee Review, Modern Fiction Studies, Comparative Literature, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, College English, Notes & Queries, ESQ, World Literature Today, The Arnoldian, etc. His papers have been widely cited and indexed in all the Humanities Indices and reviews of English scholarship across the world.

Long before English in India (its polemical history, traditions and practice) became a major subspecialty in English Studies, Nagarajan wrote and lectured on this subject through the late 70’s, beginning with his much-cited and controversial valedictory address at Poona University while relinquishing his Chair in 1979. That address became the draft of his “Decline of English in India: Some Historical Notes” (College English, 43. 7, 1981: 663–70) excerpts and versions of which later appeared in several Indian periodicals and magazines, and has ever since remained central to our arguments for and against its thesis. To have initiated, and sustained such a discussion for well over three decades, is no vanity. Nagarajan was writing at a time when English was being reconfigured as a language, discipline of thought, and an academic subject proffering supple confusions of commitment to its students in most postcolonial centres and English-speaking countries.

At the University of Hyderabad, Nagarajan left lasting imprint on a variety of academic and professional subjects such as administrative reforms, university governance, welfare schemes, library management, professional advancement and training bringing within its ambit the Campus School, and the departments and schools of study. The Humanities curricular reforms were always uppermost in his mind. So were matters pertaining to such fledgling centres (such as the CCL in 1989) which he helped build and nurture through his very last years in the University on a brief but productive stint as Professor Emeritus. Even during the most demanding days he had served as the Vice Chancellor of the University, Nagarajan was never known to have reneged on his teaching, missed crucial academic assignments such as giving lectures as the first UGC National Lecturer in English, Wilson Philological Lectures at Bombay, the Nag Memorial Lectures at Benares Hindu University, the Malegaonkar Lectures on Shakespeare at Poona besides sending quarterly reports and annual bibliographical input from India to the International Society of Shakespeare of which he was an honorary life-member.

It was indeed a matter of deep regret for him (and huge disappointment for many scholars oriented towards bibliographical and textual criticism) that two of his cherished projects had to be abandoned either because of official apathy or unavailability of continued financial and logistical support on which much of his later work depended. The first was the incomplete Union Catalogue Project funded initially by the Government of India’s Ministry of Education and Culture. At least three years of unremitting hard work by way of coordinating, monitoring, and chasing published but fugitive books and monographs in English and American Literatures catalogued in the three Presidency Universities (Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta) yielded some bibliographically rich fascicles and files of correspondence but no complete, usable, and accessible record of material students could reliably consult from afar, the prime objective of the Project. The idea of the Project is believed to have tantalized Jadavpur and Delhi, comparably equipped Departments of English like ours, to take it up from where Nagarajan had left off, but few scholars today would dare to rush in there today, their e-knowhow and resources notwithstanding. The other Project that Nagarajan had to abandon on account of intermittent ill-health and poor connectivity was a systematic study of I. A. Richards’s unpublished papers deposited at Houghton Library, Harvard and Magdalene College, Cambridge. Here, again, Nagarajan had made some headway, but he was no longer the good old researcher, at once a hedgehog and a fox in the archives, a distinction among literary scholars the poet Archilochus was fond of drawing. He made notes in longhand, kept old filing cabinets and vertical files and wrote and rewrote his work, tirelessly and conscientiously. He mentioned the “intolerable wrestle with words and meanings”— his favourite passage from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets— that continued, “happily,” according to him, until the very last conversation I have had with him on phone. Few among the English teachers I have known used to keep their erasers in order as did Nagarajan.

It was indeed a matter of deep regret for him (and huge disappointment for many scholars oriented towards bibliographical and textual criticism) that two of his cherished projects had to be abandoned either because of official apathy or unavailability of continued financial and logistical support on which much of his later work depended. The first was the incomplete Union Catalogue Project funded initially by the Government of India’s Ministry of Education and Culture. At least three years of unremitting hard work by way of coordinating, monitoring, and chasing published but fugitive books and monographs in English and American Literatures catalogued in the three Presidency Universities (Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta) yielded some bibliographically rich fascicles and files of correspondence but no complete, usable, and accessible record of material students could reliably consult from afar, the prime objective of the Project. The idea of the Project is believed to have tantalized Jadavpur and Delhi, comparably equipped Departments of English like ours, to take it up from where Nagarajan had left off, but few scholars today would dare to rush in there today, their e-knowhow and resources notwithstanding. The other Project that Nagarajan had to abandon on account of intermittent ill-health and poor connectivity was a systematic study of I. A. Richards’s unpublished papers deposited at Houghton Library, Harvard and Magdalene College, Cambridge. Here, again, Nagarajan had made some headway, but he was no longer the good old researcher, at once a hedgehog and a fox in the archives, a distinction among literary scholars the poet Archilochus was fond of drawing. He made notes in longhand, kept old filing cabinets and vertical files and wrote and rewrote his work, tirelessly and conscientiously. He mentioned the “intolerable wrestle with words and meanings”— his favourite passage from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets— that continued, “happily,” according to him, until the very last conversation I have had with him on phone. Few among the English teachers I have known used to keep their erasers in order as did Nagarajan.

To conclude with Professor Viswanathan’s paean: What an impressive teacher he was! From a young age he was a contributor to top-ranking learned professional journals. His edition of Measure for Measure and the edition of King Lear he published speak volumes about his scholarship and acumen.

To conclude with Professor Viswanathan’s paean: What an impressive teacher he was! From a young age he was a contributor to top-ranking learned professional journals. His edition of Measure for Measure and the edition of King Lear he published speak volumes about his scholarship and acumen.

He walked tall in the field.

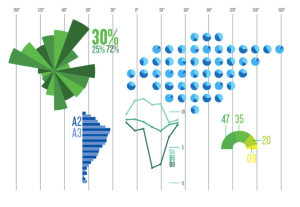

The 15 in the title above, is the overall ranking of the UoH, relative to all Indian institutions, based on our publications in all scientific fields, with 6, 8, and 22 being the rankings separately in Chemistry, Life Sciences and Physics. This is for the year 1 September 2013 to 31 August 2014, and presumably other time periods can be queried on the NI site as well.

The 15 in the title above, is the overall ranking of the UoH, relative to all Indian institutions, based on our publications in all scientific fields, with 6, 8, and 22 being the rankings separately in Chemistry, Life Sciences and Physics. This is for the year 1 September 2013 to 31 August 2014, and presumably other time periods can be queried on the NI site as well.

One of the questions playing on my mind, for instance is how many Schools of study should there be in the University? At present we have 12, but clearly we don’t cover all the areas of studies that a University should or could have. The manner in which we grow is therefore important, and there are many models that are available to us. There is admittedly a chicken and egg situation: What should one do first? We could decide by fiat or by committee (a near impossibility!) as to what is desirable. Or we could start courses- hit the ground running- and then worry about getting faculty. Or we can wait for someone else to tell us what to do. As it happens, all these models have been employed at the UoH at one time or the other in the past, and there is always an

One of the questions playing on my mind, for instance is how many Schools of study should there be in the University? At present we have 12, but clearly we don’t cover all the areas of studies that a University should or could have. The manner in which we grow is therefore important, and there are many models that are available to us. There is admittedly a chicken and egg situation: What should one do first? We could decide by fiat or by committee (a near impossibility!) as to what is desirable. Or we could start courses- hit the ground running- and then worry about getting faculty. Or we can wait for someone else to tell us what to do. As it happens, all these models have been employed at the UoH at one time or the other in the past, and there is always an

Professor Bapiraju (of the School of Computer and Information Sciences and Coordinator of CNCS) wrote in to tell me that the article in the journal Neurology (the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology) that went online yesterday was the product of collaboration among CNCS, NIMS and Osmania University, as part of a Cognitive Science Initiative project funded by the Department of Science and Technology. The full list of authors of the paper, Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status, are Suvarna Alladi, Thomas H. Bak, Vasanta Duggirala, Bapiraju Surampudi, Mekala Shailaja, Anuj Kumar Shukla, Jaydip Ray Chaudhuri, and Subhash Kaul, Anuj Shukla being an M. Phil. student of the Centre, while the other authors are at NIMS, OU, and Edinburgh.

Professor Bapiraju (of the School of Computer and Information Sciences and Coordinator of CNCS) wrote in to tell me that the article in the journal Neurology (the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology) that went online yesterday was the product of collaboration among CNCS, NIMS and Osmania University, as part of a Cognitive Science Initiative project funded by the Department of Science and Technology. The full list of authors of the paper, Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status, are Suvarna Alladi, Thomas H. Bak, Vasanta Duggirala, Bapiraju Surampudi, Mekala Shailaja, Anuj Kumar Shukla, Jaydip Ray Chaudhuri, and Subhash Kaul, Anuj Shukla being an M. Phil. student of the Centre, while the other authors are at NIMS, OU, and Edinburgh.