Some years ago, a friend of mine at JNU proudly told me about a book that he had picked up from the library “sale”, a book that had once belonged to D D Kosambi (DDK). Apparently it had not been checked out for years, and was therefore deemed unworthy of staying on in the library, as if finding a place on the library shelf was just some sort of evolutionary game, a survival of the fittest and no more…

Some years ago, a friend of mine at JNU proudly told me about a book that he had picked up from the library “sale”, a book that had once belonged to D D Kosambi (DDK). Apparently it had not been checked out for years, and was therefore deemed unworthy of staying on in the library, as if finding a place on the library shelf was just some sort of evolutionary game, a survival of the fittest and no more…

The JNU had, at some point in time, acquired Kosambi’s personal collection of books, that was, according to Mr R P Nene (DDK’s friend and assistant, in an interview in June 1985) “sold by his family after his death to the JNU at the cost of Rs. 75, 000.” Details of how this happened are not too clear- Kosambi died in 1966, the JNU was founded in 1969, and the initial seed of the JNU library was that of the “prestigious Indian School of International Studies which was later merged with Jawaharlal Nehru University.” Our website goes on to say that the “JNU Library is a depository of all Govt. publications and publications of some important International Organisations like WHO, European Union, United Nations and its allied agencies etc. The Central Library is knowledge hub of Jawaharlal Nehru University, It provides comprehensive access to books, journals, theses and dissertations, reports, surveys covering diverse disciplines.”

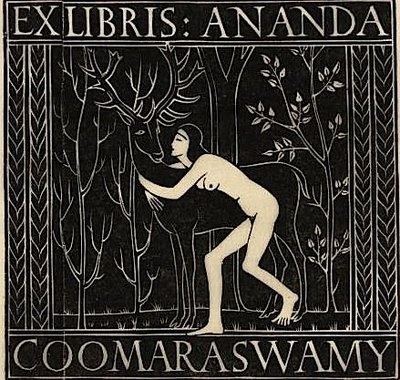

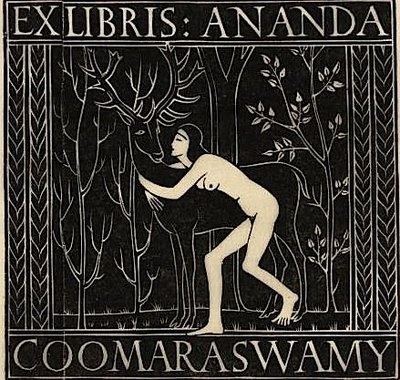

The amount paid suggests that the books were viewed as very valuable: Rs 75K in the late 1960’s was a huge sum of money. And given that, it was quite amazing that the collection had not been kept as one, but the books had apparently been shelved by subject (!) and were then like any other books, and so subject to the periodic culling that most libraries undertake to clear shelves and make space for new books. (In some sense I was not too surprised, having myself bought a book that had been owned by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy and that had somehow made its way to Princeton. The initials AKC were pencilled in on the first page, but apart from the bookplate, there was little else to show that it had been his. Unfortunately that book is no longer with me, and in hindsight, I think that when libraries acquire collections from scholars of note, they should make some attempt to keep the collections intact. Mercifully the JNU has done that now with more recent acquisitions..).

The amount paid suggests that the books were viewed as very valuable: Rs 75K in the late 1960’s was a huge sum of money. And given that, it was quite amazing that the collection had not been kept as one, but the books had apparently been shelved by subject (!) and were then like any other books, and so subject to the periodic culling that most libraries undertake to clear shelves and make space for new books. (In some sense I was not too surprised, having myself bought a book that had been owned by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy and that had somehow made its way to Princeton. The initials AKC were pencilled in on the first page, but apart from the bookplate, there was little else to show that it had been his. Unfortunately that book is no longer with me, and in hindsight, I think that when libraries acquire collections from scholars of note, they should make some attempt to keep the collections intact. Mercifully the JNU has done that now with more recent acquisitions..).

Nevertheless, a chance conversation shortly thereafter on the vagaries of libraries and the nature of intellectual inheritances started me off on my exploration of Kosambi and his mathematics. The idea was, on the face of, a simple one. What was the extent of Kosambi’s mathematical contributions compared to, say, his contributions to history or numismatics. How would the math stack up? Having been in TIFR before I came to JNU, I had also heard of how he travelled from Pune to Bombay every day on the Deccan Queen, how he was fired from TIFR, etc. etc. But I also found out that precious little was known of DDK’s other life by the historians. That the mathematics was too different and far too difficult is all too true, but still.

Nevertheless, a chance conversation shortly thereafter on the vagaries of libraries and the nature of intellectual inheritances started me off on my exploration of Kosambi and his mathematics. The idea was, on the face of, a simple one. What was the extent of Kosambi’s mathematical contributions compared to, say, his contributions to history or numismatics. How would the math stack up? Having been in TIFR before I came to JNU, I had also heard of how he travelled from Pune to Bombay every day on the Deccan Queen, how he was fired from TIFR, etc. etc. But I also found out that precious little was known of DDK’s other life by the historians. That the mathematics was too different and far too difficult is all too true, but still.

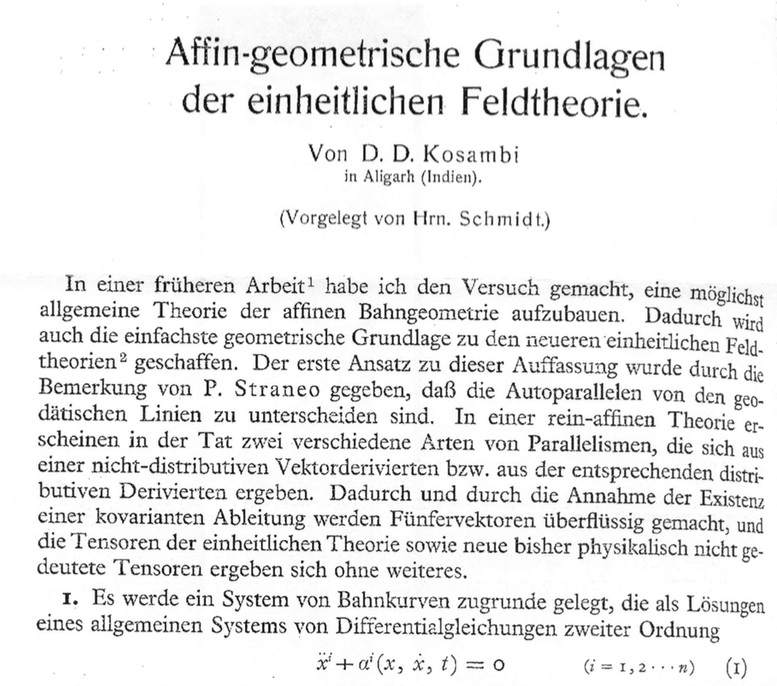

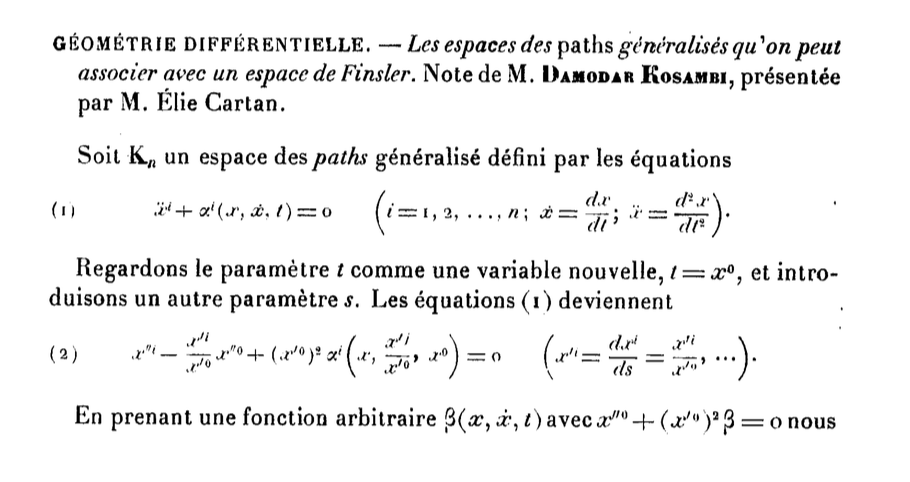

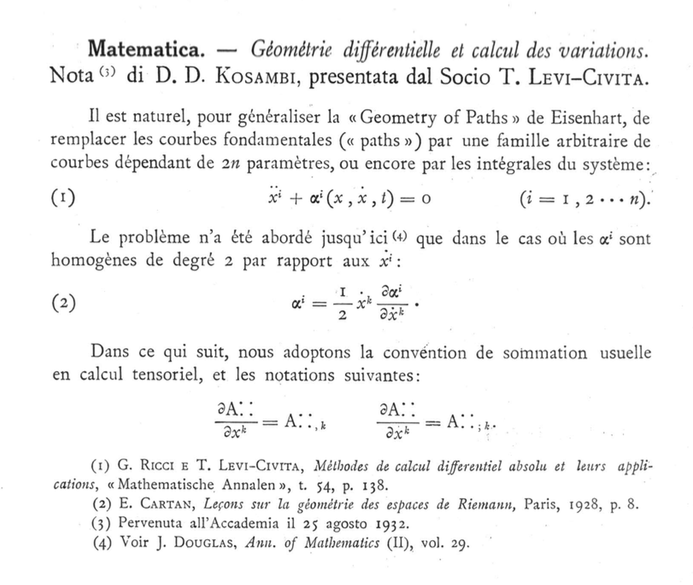

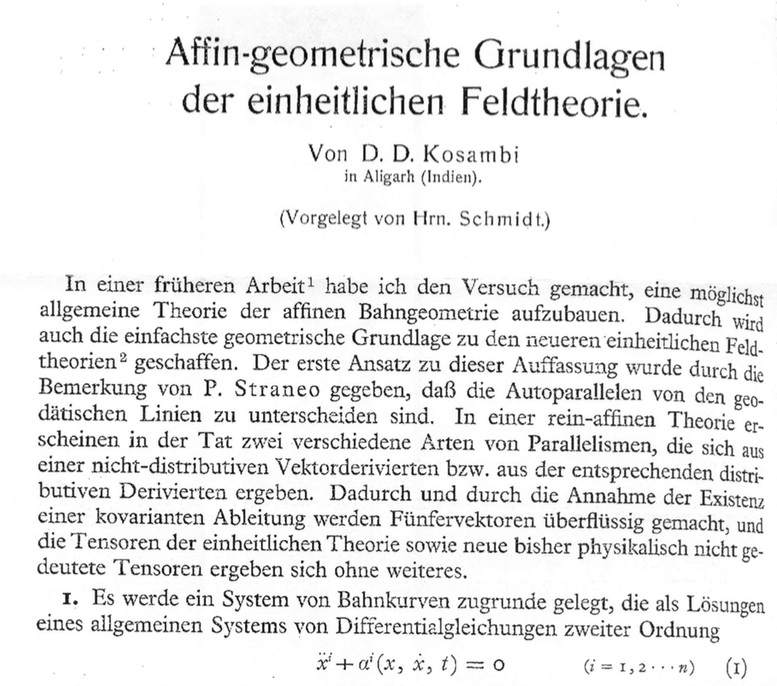

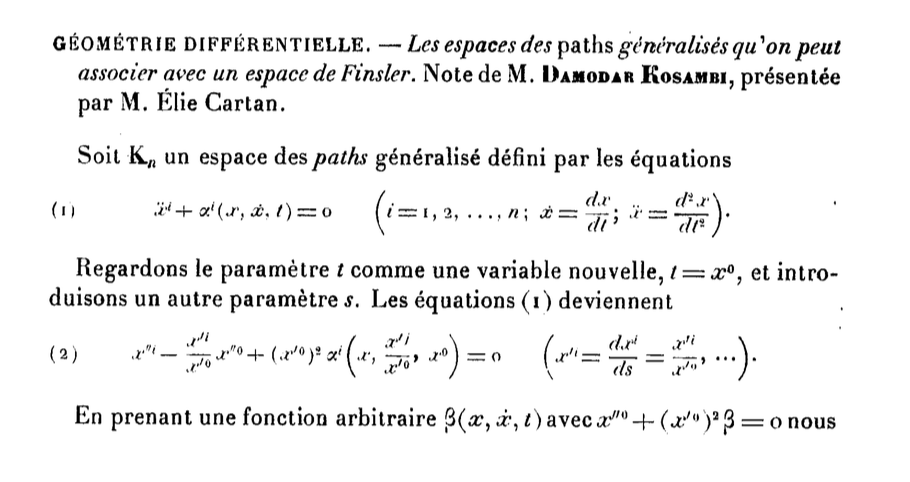

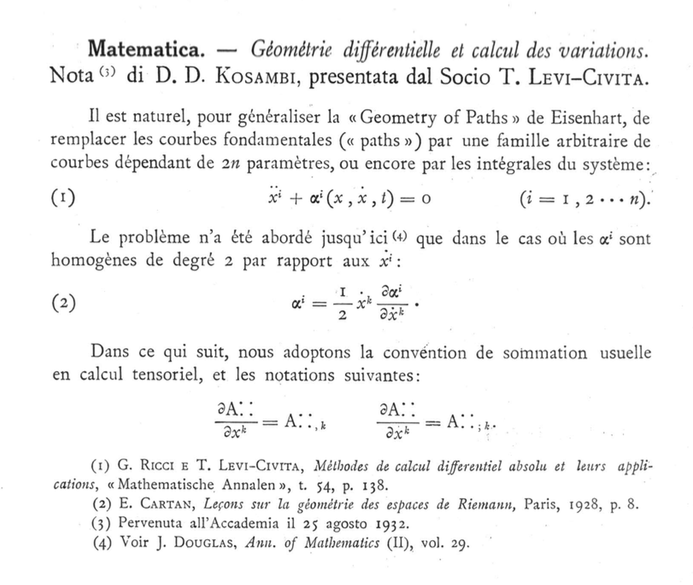

To start with, I thought it would be good to put together his life mathematical, namely all his math and stats papers. Much of that was on the web, except that it was in bits and pieces, and all over the place. No single bibliography was accurate, and no matter where I looked, there were gaps. Many of the Indian journals where he published were not (and still are not) digitized. Some of the names that were given in the existing lists were incomplete or incorrect, many papers were missing. The Rendiconti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei or the Sitzungsberichten der Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische klasse were both uncommon journals that were impossible to locate anywhere in India, for instance. I went to the Ramanujan Institute in Chennai in late 2009, looking for copies of the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student where DDK had published a lot of his work in the 1930’s and 1940’s. It’s too depressing to recount that visit… Nothing could be located, and I left empty-handed after a wasted morning.

To start with, I thought it would be good to put together his life mathematical, namely all his math and stats papers. Much of that was on the web, except that it was in bits and pieces, and all over the place. No single bibliography was accurate, and no matter where I looked, there were gaps. Many of the Indian journals where he published were not (and still are not) digitized. Some of the names that were given in the existing lists were incomplete or incorrect, many papers were missing. The Rendiconti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei or the Sitzungsberichten der Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische klasse were both uncommon journals that were impossible to locate anywhere in India, for instance. I went to the Ramanujan Institute in Chennai in late 2009, looking for copies of the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student where DDK had published a lot of his work in the 1930’s and 1940’s. It’s too depressing to recount that visit… Nothing could be located, and I left empty-handed after a wasted morning.

In 2010, though, I was visiting professor at the University of Tokyo for a month, and luckily, the Komaba campus where I was located, housed the mathematics department and more importantly, its library. It took a few hours spread out over several days, but before long, I not only had the bulk of DDK’s papers in photocopy or in digital form, but I also discovered, via MathSciNet, of DDK’s nom de plume S. Ducray, under which name he had written four papers. I also had access to the reviews of many of his mathematical papers by others, and could see many very famous names among the reviewers. As an aside, I should add that the library of Tokyo University is one of the few that have the complete sets of Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student, including the volumes published during the World War II years, when Japan and India were on different sides…

In 2010, though, I was visiting professor at the University of Tokyo for a month, and luckily, the Komaba campus where I was located, housed the mathematics department and more importantly, its library. It took a few hours spread out over several days, but before long, I not only had the bulk of DDK’s papers in photocopy or in digital form, but I also discovered, via MathSciNet, of DDK’s nom de plume S. Ducray, under which name he had written four papers. I also had access to the reviews of many of his mathematical papers by others, and could see many very famous names among the reviewers. As an aside, I should add that the library of Tokyo University is one of the few that have the complete sets of Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student, including the volumes published during the World War II years, when Japan and India were on different sides…

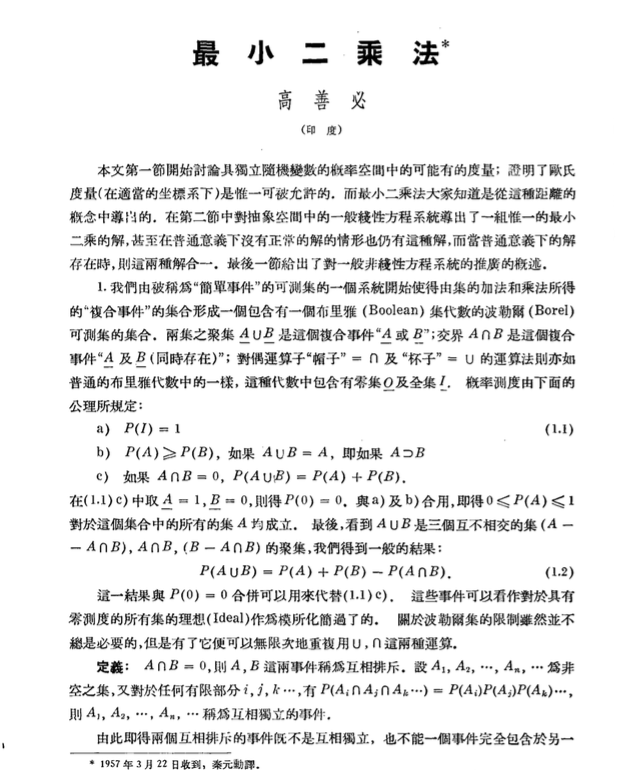

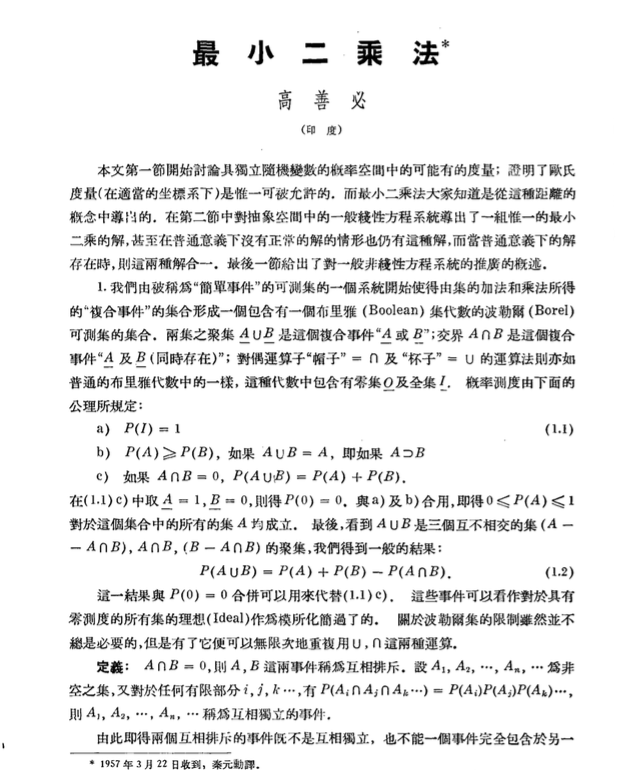

In addition to English, DDK wrote in German and French, and there were Japanese as well as Chinese translations, at least one of which was the original language of publication. I was able to put together the titles of about 67 papers that were on mathematics or statistics and then set about getting physical copies of all of them. Some were easy- the Indian Society for Agricultural Statistics is on Pusa Road in New Delhi, the Indian Academy of Sciences has digitised its entire collection, and so on. For some I was lucky- I was invited to Hokkaido University in Sapporo from where the journal Tensor (New Series) is published, so I was able to get two of his papers, and work took me to the Academia Sinica in Taipei where I was able to get one more paper that he had originally published in Chinese. The papers in Comptes Rendu (in French) came via an old student who was in Paris, the one in the Prussian Academy journal from a friend who used to work for JSTOR, and the paper in the New Indian Antiquary via an old student who was in Chicago. Some of this vast international effort was probably unnecessary (in the sense that I could have found some things closer home and with less sturm und drang if I were a properly trained historian of science) but it all seemed good fun as it was happening. And it was, so to speak, a side business anyhow…

In addition to English, DDK wrote in German and French, and there were Japanese as well as Chinese translations, at least one of which was the original language of publication. I was able to put together the titles of about 67 papers that were on mathematics or statistics and then set about getting physical copies of all of them. Some were easy- the Indian Society for Agricultural Statistics is on Pusa Road in New Delhi, the Indian Academy of Sciences has digitised its entire collection, and so on. For some I was lucky- I was invited to Hokkaido University in Sapporo from where the journal Tensor (New Series) is published, so I was able to get two of his papers, and work took me to the Academia Sinica in Taipei where I was able to get one more paper that he had originally published in Chinese. The papers in Comptes Rendu (in French) came via an old student who was in Paris, the one in the Prussian Academy journal from a friend who used to work for JSTOR, and the paper in the New Indian Antiquary via an old student who was in Chicago. Some of this vast international effort was probably unnecessary (in the sense that I could have found some things closer home and with less sturm und drang if I were a properly trained historian of science) but it all seemed good fun as it was happening. And it was, so to speak, a side business anyhow…

In the end there are only two works by DDK that are now not available, both books. One was sent to the publishers a few days before he died: this manuscript, on Prime Numbers was never found. Its loss was not followed up, and now it is too late. The other book, on Path Geometry was submitted to Marston Morse at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and that was also never published. It so happened that I had spent a sabbatical year there in 2004-5, and had actually met Mrs Morse, so I wrote to ask her if there was any record of the submitted manuscript among the Morse papers (Marston Morse had passed on in 1977). By then Mrs Morse was in her hundredth year, and although a search was made, nothing could be located. Other than these two “missing works”, copies of all other papers can be had for the asking; a listing of all DDK’s papers is now available in the Indian Academy of Sciences Repository of publications by Fellows, DDK having been elected one in 1935.

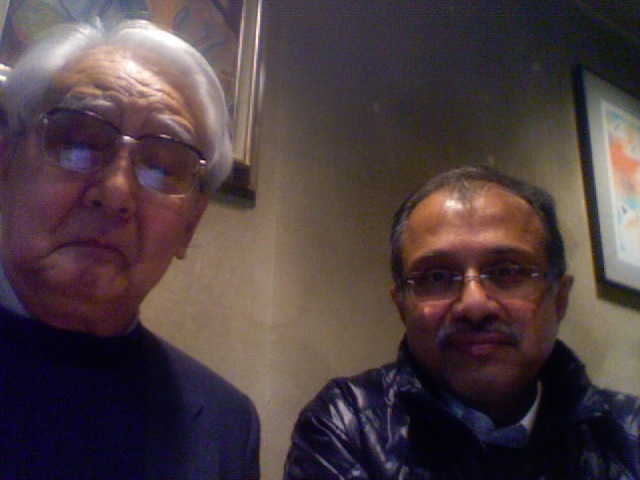

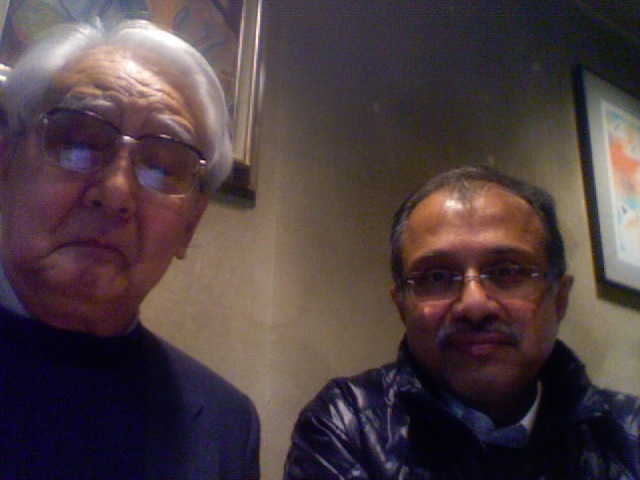

But also in 2010, I was introduced to Meera Kosambi via email (I was still in Tokyo then) and she in turn introduced me to Professor Toshio Yamazaki who had by then retired from the History Department at Tokyo University, but who had been a student of DDK and H D Sankalia at Deccan College in the late 1950’s to early 1960’s. We met for a coffee one morning, and apart from taking a grim picture (a pre-smartphone selfie, as it were!) to mark the occasion, we chatted about DDK and Yamazaki-san’s Indian experiences. Getting to know Meera Kosambi – Meeratai as she insisted she be addressed- turned out to be a major turning point in this enterprise. For one thing, it made it just that much more concrete and worth the effort involved when I realised that even she was largely unaware of her father’s contributions and the complexity of his mathematical reputation. A few conversations with her cleared up many things – of how he never had the Ph D degree for instance, or of the family dog Bonzo and how he had grown so fat that DDK called him a pig (dukker in Marathi) and so on. All of which was summarized in an article that was published in EPW in 2012 on the mathematical legacy of DDK, the abstract of which I quote below:

But also in 2010, I was introduced to Meera Kosambi via email (I was still in Tokyo then) and she in turn introduced me to Professor Toshio Yamazaki who had by then retired from the History Department at Tokyo University, but who had been a student of DDK and H D Sankalia at Deccan College in the late 1950’s to early 1960’s. We met for a coffee one morning, and apart from taking a grim picture (a pre-smartphone selfie, as it were!) to mark the occasion, we chatted about DDK and Yamazaki-san’s Indian experiences. Getting to know Meera Kosambi – Meeratai as she insisted she be addressed- turned out to be a major turning point in this enterprise. For one thing, it made it just that much more concrete and worth the effort involved when I realised that even she was largely unaware of her father’s contributions and the complexity of his mathematical reputation. A few conversations with her cleared up many things – of how he never had the Ph D degree for instance, or of the family dog Bonzo and how he had grown so fat that DDK called him a pig (dukker in Marathi) and so on. All of which was summarized in an article that was published in EPW in 2012 on the mathematical legacy of DDK, the abstract of which I quote below:

Today, D D Kosambi’s significance as a historian greatly overshadows his reputation and contributions in mathematics. Kosambi simultaneously worked in both areas for much of his adult life, and to understand the body of his work either in the social sciences or in mathematics, an appreciation of the complementarity of his interests is essential. An understanding of Kosambi the historian can only be enhanced by an appreciation of Kosambi the mathematician. In a fundamental way, Kosambi embodied the multidisciplinary approach, channelling diverse interests – indeed combining them – to create scholarship of high order.

The same article was published in a book, Unsettling the Past (Permanent Black, 2012) that Meera Kosambi brought out later that year. Perhaps conscious of the limited time that was left to her, she was keen to see the intellectual legacies of Kosambi Père et Fils firmly in place. (For whatever reason, and in my opinion unfairly, she constantly judged herself by their mythical standards and fell short. As indeed, who would not…) In the aftermath of the the D D Kosambi centenary (2007-8), Meeratai published at a furious pace- Dharmanand Kosambi’s writings in translation, his autobiography Nivedan, Gender, Culture, and Performance: Marathi Theatre and Cinema before Independence, Crossing Thresholds: Feminist Essays in Social History, Mahatma Gandhi and Prema Kantak: Exploring a Relationship, Exploring History, Feminist Vision or ‘Treason Against Men’?: Kashibai Kanitkar and the Engendering of Marathi Literature, Women Writing Gender: Marathi Fiction Before Independence, something like ten books in the five years that I knew her. She always had a book to write, and as those who knew her more closely told me, when the end was near, she was ready to go only after she finished the very last bits on her forthcoming Pandita Ramabai: Life and landmark writings.

Meera Kosambi also gave the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library most of what she could of DDK’s papers and writings so that they could be properly archived. But fortunately, this was after she let me, and more importantly, Rajaram Nityananda, then Director of the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics in Pune look through them. In the process Rajaram had many of the papers digitised, and there was much in there that was (and still is) waiting to be discovered – unfinished manuscripts, unpublished notes, letters and so forth.

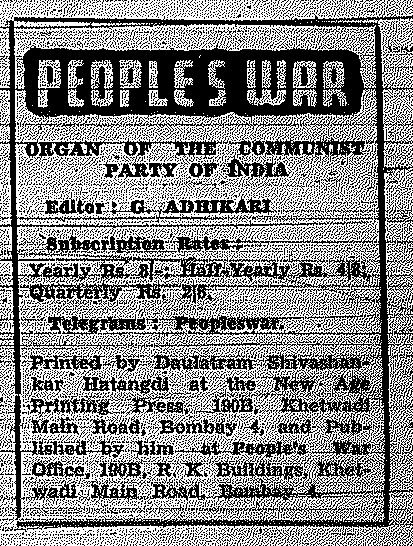

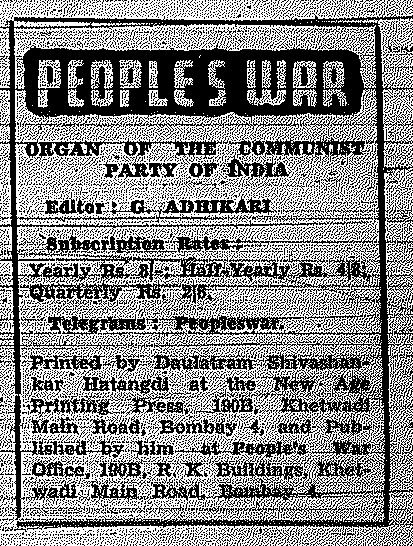

In particular, there are typescripts of many articles and notes. DDK’s notebooks from Harvard, where he had taken lecture notes as an undergraduate are also among the papers. And not just mathematics notebooks, either- in short, material that is ripe for some amount of scholarly analysis. For instance, there is an article on C V Raman, (the somewhat more palatable) half of which was published in People’s War in 1945 by “Indian Scientist”. The latter half of the article seems to have been (correctly, in the opinion of several who have read it) deemed to be left better unsaid. There are also the edited typescripts of several essays.

In particular, there are typescripts of many articles and notes. DDK’s notebooks from Harvard, where he had taken lecture notes as an undergraduate are also among the papers. And not just mathematics notebooks, either- in short, material that is ripe for some amount of scholarly analysis. For instance, there is an article on C V Raman, (the somewhat more palatable) half of which was published in People’s War in 1945 by “Indian Scientist”. The latter half of the article seems to have been (correctly, in the opinion of several who have read it) deemed to be left better unsaid. There are also the edited typescripts of several essays.

And then there are letters, several of them. Like many in the pre-email era, DDK was a chatty correspondent. He made good and lasting friends as a teenager and young adult, those that stood by him pretty much through his life. Letters to the (R. J.) Conklins- a few of which have appeared in Unsettling give an unusual and somewhat American view of India in the 1930’s in the period when the freedom movement gained ground. Norbert Wiener remained a close friend, and professionally, he remained close to André Weil through his life, and for a brief while to Élie Cartan and Tulio Levi-Civita as well. Their correspondence, what remains of it, needs to be seen, as also his letters to Divyabhanusinh Chavda. The pictures that emerge of DDK, warts and all, need to be confronted. Of his personal angularities DDK was all too aware as he was of his many talents and his intellect. He was unapologetic, but also, occasionally, un-self-critical, refusing to see what he might have achieved through compromise and (academic) collaboration. As he says, when speaking of the Riemann debacle, at the end of his autobiographical essay, Adventure into the Unknown, with ample self-justification and more than a hint of self pity,

“Let me admit at once that I made every sort of mistake in the first presentation. There is no excuse for this, though there were strong reasons: I had to fight for my results over three long years between waves of agony from chronic arthritis, against massive daily doses of aspirin, splitting headaches, fever, lack of assistance and steady disparagement. It was much more difficult to discover good mathematicians who were able to see the main point of the proof than it had been to make the original mathematical discovery. How much of this is due to my own disagreeable personality and what part to the spirit of a tight medieval guild that rules mathematical circles in certain countries with an `affluent society’ need not be considered here. There is a surely a great deal to be said for the notion that the success of science is fundamentally related to the particular form of society”.

Not being au fait with either the historian or the mathematician’s insider view of DDK, I had to discover many things afresh, such as his use of pseudonyms. This is one area where it is clear that some serious work is needed, given the range of his contributions; I have only poor hypotheses as to why he did this. In three articles, DDK signed himself as Ahriman, Vidyarthi, Indian Scientist, but after he invented the persona of S. Ducray in the early 1960’s he used it professionally in no less than four papers. Meanwhile, Kosambi as Kosambi was publishing Myth and Reality in 1963, and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline in 1965, as well as the occasional mathematics paper sent off to select journals! In many letters to friends, DDK signs off as Ducray; in one of the papers in the Journal of the University of Bombay, Ducray says “My debt to Prof. Kosambi is obvious”, while in another, the acknowledgment reads “This paper would not have been possible without the constant labour of Prof. D. D. Kosambi.”

Not being au fait with either the historian or the mathematician’s insider view of DDK, I had to discover many things afresh, such as his use of pseudonyms. This is one area where it is clear that some serious work is needed, given the range of his contributions; I have only poor hypotheses as to why he did this. In three articles, DDK signed himself as Ahriman, Vidyarthi, Indian Scientist, but after he invented the persona of S. Ducray in the early 1960’s he used it professionally in no less than four papers. Meanwhile, Kosambi as Kosambi was publishing Myth and Reality in 1963, and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline in 1965, as well as the occasional mathematics paper sent off to select journals! In many letters to friends, DDK signs off as Ducray; in one of the papers in the Journal of the University of Bombay, Ducray says “My debt to Prof. Kosambi is obvious”, while in another, the acknowledgment reads “This paper would not have been possible without the constant labour of Prof. D. D. Kosambi.”

Weird. DDK had, as has now been recounted several times, been responsible for the first mention of the name Bourbaki in the mathematics literature. Although the name Bourbaki is a collective pseudonym for a group of (largely French) mathematicians, there is a somewhat light-hearted frivolity to the naming part of the enterprise while the mathematics itself is of the highest order. Not so with the Ducray business, and it is difficult to see it through a hagiographer’s eye, as a piece of childish chicanery and no more.

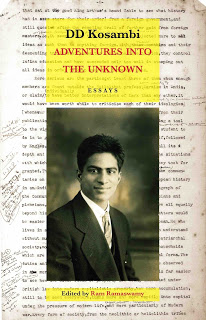

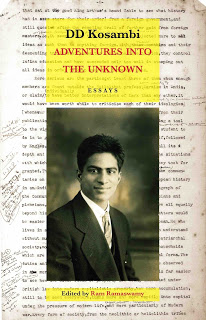

Clearly there is much more work that needs to be done on Kosambi himself and this goes beyond putting together his articles and situating them. This blogpost started off as a way of my keeping track and not just a vehicle for self-promotion. Two of the discursive essays that were found among his papers have now been printed for the first time in the book Adventures into the Unknown that I have edited, and which is published by Three Essays Collective, Gurgaon. My “Collected Works” of DDK project is also under way, though it will probably take the better part of this year to complete, and will become a “Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics” in the process.

Clearly there is much more work that needs to be done on Kosambi himself and this goes beyond putting together his articles and situating them. This blogpost started off as a way of my keeping track and not just a vehicle for self-promotion. Two of the discursive essays that were found among his papers have now been printed for the first time in the book Adventures into the Unknown that I have edited, and which is published by Three Essays Collective, Gurgaon. My “Collected Works” of DDK project is also under way, though it will probably take the better part of this year to complete, and will become a “Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics” in the process.

Within a relatively short working life – he died at 59 – DDK made many original and fundamental contributions to many aspects of scholarly enquiry. The Promethean epithet applies very aptly to Kosambi, though- when the Gods give such gifts, and they do not give these to many, there is a price to be paid… A verse from Bhartṛhari that DDK surely knew (having three monumental contributions on the works of the 7th c. poet) says it all too well:

Nor do the gods appear in warrior’s armour clad

To strike them down with sword and spear

Those whom they would destroy

They first make mad.

Charusita Chakravarty, Professor of Chemistry at the IIT Delhi died last Tuesday, 29 March 2016.

Charusita Chakravarty, Professor of Chemistry at the IIT Delhi died last Tuesday, 29 March 2016.

My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at

My friend and colleague, Deepak Kumar, passed away all of a sudden late Monday (25th January) night. I had seen him that day, sharing a cup of tea with another member of the faculty in the afternoon sun on the lawns of the School of Physical Sciences at  Some years ago, a friend of mine at JNU proudly told me about a book that he had picked up from the library “sale”, a book that had once belonged to D D Kosambi (DDK). Apparently it had not been checked out for years, and was therefore deemed unworthy of staying on in the library, as if finding a place on the library shelf was just some sort of evolutionary game, a survival of the fittest and no more…

Some years ago, a friend of mine at JNU proudly told me about a book that he had picked up from the library “sale”, a book that had once belonged to D D Kosambi (DDK). Apparently it had not been checked out for years, and was therefore deemed unworthy of staying on in the library, as if finding a place on the library shelf was just some sort of evolutionary game, a survival of the fittest and no more… The amount paid suggests that the books were viewed as very valuable: Rs 75K in the late 1960’s was a huge sum of money. And given that, it was quite amazing that the collection had not been kept as one, but the books had apparently been shelved by subject (!) and were then like any other books, and so subject to the periodic culling that most libraries undertake to clear shelves and make space for new books. (In some sense I was not too surprised, having myself bought a book that had been owned by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy and that had somehow made its way to Princeton. The initials AKC were pencilled in on the first page, but apart from the bookplate, there was little else to show that it had been his. Unfortunately that book is no longer with me, and in hindsight, I think that when libraries acquire collections from scholars of note, they should make some attempt to keep the collections intact. Mercifully the JNU has done that now with more recent acquisitions..).

The amount paid suggests that the books were viewed as very valuable: Rs 75K in the late 1960’s was a huge sum of money. And given that, it was quite amazing that the collection had not been kept as one, but the books had apparently been shelved by subject (!) and were then like any other books, and so subject to the periodic culling that most libraries undertake to clear shelves and make space for new books. (In some sense I was not too surprised, having myself bought a book that had been owned by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy and that had somehow made its way to Princeton. The initials AKC were pencilled in on the first page, but apart from the bookplate, there was little else to show that it had been his. Unfortunately that book is no longer with me, and in hindsight, I think that when libraries acquire collections from scholars of note, they should make some attempt to keep the collections intact. Mercifully the JNU has done that now with more recent acquisitions..). Nevertheless, a chance conversation shortly thereafter on the vagaries of libraries and the nature of intellectual inheritances started me off on my exploration of Kosambi and his mathematics. The idea was, on the face of, a simple one. What was the extent of Kosambi’s mathematical contributions compared to, say, his contributions to history or numismatics. How would the math stack up? Having been in TIFR before I came to JNU, I had also heard of how he travelled from Pune to Bombay every day on the Deccan Queen, how he was fired from TIFR, etc. etc. But I also found out that precious little was known of DDK’s other life by the historians. That the mathematics was too different and far too difficult is all too true, but still.

Nevertheless, a chance conversation shortly thereafter on the vagaries of libraries and the nature of intellectual inheritances started me off on my exploration of Kosambi and his mathematics. The idea was, on the face of, a simple one. What was the extent of Kosambi’s mathematical contributions compared to, say, his contributions to history or numismatics. How would the math stack up? Having been in TIFR before I came to JNU, I had also heard of how he travelled from Pune to Bombay every day on the Deccan Queen, how he was fired from TIFR, etc. etc. But I also found out that precious little was known of DDK’s other life by the historians. That the mathematics was too different and far too difficult is all too true, but still. To start with, I thought it would be good to put together his life mathematical, namely all his math and stats papers. Much of that was on the web, except that it was in bits and pieces, and all over the place. No single bibliography was accurate, and no matter where I looked, there were gaps. Many of the Indian journals where he published were not (and still are not) digitized. Some of the names that were given in the existing lists were incomplete or incorrect, many papers were missing. The Rendiconti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei or the Sitzungsberichten der Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische klasse were both uncommon journals that were impossible to locate anywhere in India, for instance. I went to the Ramanujan Institute in Chennai in late 2009, looking for copies of the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student where DDK had published a lot of his work in the 1930’s and 1940’s. It’s too depressing to recount that visit… Nothing could be located, and I left empty-handed after a wasted morning.

To start with, I thought it would be good to put together his life mathematical, namely all his math and stats papers. Much of that was on the web, except that it was in bits and pieces, and all over the place. No single bibliography was accurate, and no matter where I looked, there were gaps. Many of the Indian journals where he published were not (and still are not) digitized. Some of the names that were given in the existing lists were incomplete or incorrect, many papers were missing. The Rendiconti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei or the Sitzungsberichten der Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische klasse were both uncommon journals that were impossible to locate anywhere in India, for instance. I went to the Ramanujan Institute in Chennai in late 2009, looking for copies of the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student where DDK had published a lot of his work in the 1930’s and 1940’s. It’s too depressing to recount that visit… Nothing could be located, and I left empty-handed after a wasted morning. In 2010, though, I was visiting professor at the University of Tokyo for a month, and luckily, the Komaba campus where I was located, housed the mathematics department and more importantly, its library. It took a few hours spread out over several days, but before long, I not only had the bulk of DDK’s papers in photocopy or in digital form, but I also discovered, via MathSciNet, of DDK’s nom de plume S. Ducray, under which name he had written four papers. I also had access to the reviews of many of his mathematical papers by others, and could see many very famous names among the reviewers. As an aside, I should add that the library of Tokyo University is one of the few that have the complete sets of Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student, including the volumes published during the World War II years, when Japan and India were on different sides…

In 2010, though, I was visiting professor at the University of Tokyo for a month, and luckily, the Komaba campus where I was located, housed the mathematics department and more importantly, its library. It took a few hours spread out over several days, but before long, I not only had the bulk of DDK’s papers in photocopy or in digital form, but I also discovered, via MathSciNet, of DDK’s nom de plume S. Ducray, under which name he had written four papers. I also had access to the reviews of many of his mathematical papers by others, and could see many very famous names among the reviewers. As an aside, I should add that the library of Tokyo University is one of the few that have the complete sets of Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society and Mathematics Student, including the volumes published during the World War II years, when Japan and India were on different sides… In addition to English, DDK wrote in German and French, and there were Japanese as well as Chinese translations, at least one of which was the original language of publication. I was able to put together the titles of about 67 papers that were on mathematics or statistics and then set about getting physical copies of all of them. Some were easy- the Indian Society for Agricultural Statistics is on Pusa Road in New Delhi, the Indian Academy of Sciences has digitised its entire collection, and so on. For some I was lucky- I was invited to Hokkaido University in Sapporo from where the journal Tensor (New Series) is published, so I was able to get two of his papers, and work took me to the Academia Sinica in Taipei where I was able to get one more paper that he had originally published in Chinese. The papers in Comptes Rendu (in French) came via an old student who was in Paris, the one in the Prussian Academy journal from a friend who used to work for JSTOR, and the paper in the New Indian Antiquary via an old student who was in Chicago. Some of this vast international effort was probably unnecessary (in the sense that I could have found some things closer home and with less sturm und drang if I were a properly trained historian of science) but it all seemed good fun as it was happening. And it was, so to speak, a side business anyhow…

In addition to English, DDK wrote in German and French, and there were Japanese as well as Chinese translations, at least one of which was the original language of publication. I was able to put together the titles of about 67 papers that were on mathematics or statistics and then set about getting physical copies of all of them. Some were easy- the Indian Society for Agricultural Statistics is on Pusa Road in New Delhi, the Indian Academy of Sciences has digitised its entire collection, and so on. For some I was lucky- I was invited to Hokkaido University in Sapporo from where the journal Tensor (New Series) is published, so I was able to get two of his papers, and work took me to the Academia Sinica in Taipei where I was able to get one more paper that he had originally published in Chinese. The papers in Comptes Rendu (in French) came via an old student who was in Paris, the one in the Prussian Academy journal from a friend who used to work for JSTOR, and the paper in the New Indian Antiquary via an old student who was in Chicago. Some of this vast international effort was probably unnecessary (in the sense that I could have found some things closer home and with less sturm und drang if I were a properly trained historian of science) but it all seemed good fun as it was happening. And it was, so to speak, a side business anyhow… But also in 2010, I was introduced to

But also in 2010, I was introduced to  In particular, there are typescripts of many articles and notes. DDK’s notebooks from Harvard, where he had taken lecture notes as an undergraduate are also among the papers. And not just mathematics notebooks, either- in short, material that is ripe for some amount of scholarly analysis. For instance, there is an article on C V Raman, (the somewhat more palatable) half of which was published in People’s War in 1945 by “Indian Scientist”. The latter half of the article seems to have been (correctly, in the opinion of several who have read it) deemed to be left better unsaid. There are also the edited typescripts of several essays.

In particular, there are typescripts of many articles and notes. DDK’s notebooks from Harvard, where he had taken lecture notes as an undergraduate are also among the papers. And not just mathematics notebooks, either- in short, material that is ripe for some amount of scholarly analysis. For instance, there is an article on C V Raman, (the somewhat more palatable) half of which was published in People’s War in 1945 by “Indian Scientist”. The latter half of the article seems to have been (correctly, in the opinion of several who have read it) deemed to be left better unsaid. There are also the edited typescripts of several essays. Not being au fait with either the historian or the mathematician’s insider view of DDK, I had to discover many things afresh, such as his use of pseudonyms. This is one area where it is clear that some serious work is needed, given the range of his contributions; I have only poor hypotheses as to why he did this. In three articles, DDK signed himself as Ahriman, Vidyarthi, Indian Scientist, but after he invented the persona of S. Ducray in the early 1960’s he used it professionally in no less than four papers. Meanwhile, Kosambi as Kosambi was publishing Myth and Reality in 1963, and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline in 1965, as well as the occasional mathematics paper sent off to select journals! In many letters to friends, DDK signs off as Ducray; in one of the papers in the Journal of the University of Bombay, Ducray says “My debt to Prof. Kosambi is obvious”, while in another, the acknowledgment reads “This paper would not have been possible without the constant labour of Prof. D. D. Kosambi.”

Not being au fait with either the historian or the mathematician’s insider view of DDK, I had to discover many things afresh, such as his use of pseudonyms. This is one area where it is clear that some serious work is needed, given the range of his contributions; I have only poor hypotheses as to why he did this. In three articles, DDK signed himself as Ahriman, Vidyarthi, Indian Scientist, but after he invented the persona of S. Ducray in the early 1960’s he used it professionally in no less than four papers. Meanwhile, Kosambi as Kosambi was publishing Myth and Reality in 1963, and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline in 1965, as well as the occasional mathematics paper sent off to select journals! In many letters to friends, DDK signs off as Ducray; in one of the papers in the Journal of the University of Bombay, Ducray says “My debt to Prof. Kosambi is obvious”, while in another, the acknowledgment reads “This paper would not have been possible without the constant labour of Prof. D. D. Kosambi.” Clearly there is much more work that needs to be done on Kosambi himself and this goes beyond putting together his articles and situating them. This blogpost started off as a way of my keeping track and not just a vehicle for self-promotion. Two of the discursive essays that were found among his papers have now been printed for the first time in the book

Clearly there is much more work that needs to be done on Kosambi himself and this goes beyond putting together his articles and situating them. This blogpost started off as a way of my keeping track and not just a vehicle for self-promotion. Two of the discursive essays that were found among his papers have now been printed for the first time in the book